Sonia Minocha1* and Dr. Animesh Singh2

Research Scholar, Manav Rachna University, India

Associate Professor, Manav Rachna University, India

Received: 09 January 2024; Accepted: 24 January 2024; Published: 02 February 2024

Citation: Minocha, Sonia. “From Attitude to Action: Exploring the Pathway to Purchase In Organic Skincare Products.” J Skin Health Cosmet (2024): 101. DOI: 10.59462/JSHC.1.1.101

Copyright: © 2024 Minocha S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Assessing consumer attitudes towards organic skincare products is crucial in today’s competitive market. As people become more conscious of synthetic substances, animal suffering, and environmental impacts, the appeal of organic skincare is greater than ever. This paper investigates how consumer attitudes regarding organic skin care products translate into purchase intentions and subsequent shopping behaviour. The research emphasises the impact of health, environmental, and appearance consciousness on customer attitudes towards organic skin care products. The study investigates the influence of experience and subjective standards in regulating the relationship between buy intention and purchase conduct. Data was collected by random sampling. There were 498 valid replies to the survey. The Hayes process approach, psychometric characteristics, and hypothesis testing addressed the study’s research concerns. SPSS 25 and AMOS 22 are used to analyse the data. According to the study, health, environmental, and appearance consciousness are precursors to attitudes towards organic skin care products. When an attitude is created, it is converted into buying intention, which leads to actual behaviour. Past experience plays a substantial moderating impact on purchasing intention and behaviour. Subjective norms, on the other hand, fail to moderate the same relationship. The limitations and future scope of the study are discussed further in the paper’s body.

Health consciousness • Environmental consciousness • Appearance consciousness • Consumer attitude • Purchase intention • Past experience • Subjective norms

Pursuing glowing and healthy skin has resulted in a thriving skincare sector today. Organic skincare products have become a symbol of health-conscious beauty among many choices [1]. As awareness of synthetic ingredients, animal suffering, and environmental effects grows, the temptation of organic skincare is stronger than ever [2]. This study aims to elucidate the complex process by which attitudes towards organic skincare products are formed and how these attitudes contribute to purchase intentions and actual purchasing behaviour, offering valuable insights into the dynamic relationship between consumer choices and the ever-changing landscape of the cosmetics industry.

Assessing consumer attitudes regarding organic skincare products is critical in today’s competitive economy [3]. This research sets out on a journey of consumer insights that will hold the key to deciphering the ever-changing dynamics of the beauty market. This undertaking is motivated by three factors. It tackles the requirement of catering to health-conscious customers whose discriminating tastes drive demand for organic skincare solutions [4]. With rising concerns about synthetic chemicals hidden in traditional beauty regimens, people are increasingly opting towards organic alternatives [5]. Second, this research looks into the significant impact of environmental consciousness on consumer attitudes. Consumers seek products that align with their sustainability ethos in an era of increased environmental awareness [6]. By unravelling the subtle interplay between these attitudes and consumer preferences, brands may make educated decisions about sustainable sourcing, manufacturing methods, and environmentally friendly packaging solutions. Finally, it is critical to investigate the role of appearance consciousness. Consumers are increasingly looking for goods promising health benefits and physical appearance upgrades in an age where aesthetics play an important role in self-expression [7]. Researching how appearance concerns impact consumer attitudes in the intensely competitive beauty sector attracts a broader consumer base and galvanises sales.

The study delves deeper into the root cause of consumer attitudes regarding organic skincare products, deepening the curiosity by investigating how these attitudes transform into concrete purchase intentions, eventually resulting in practical purchasing behaviour. This shift is a critical point at which perception becomes action, and it is here that we discover the intricacies of consumer decision-making.

• To explore how does consumer attitude towards organic skin care products transform into purchase intention and subsequent purchasing behaviour.

• To understand the impact of health consciousness, environmental consciousness, and appearance consciousness on consumer attitude towards organic skin care products.

• To understand the moderating role of past experience and subjective norms between purchase intention and purchase behaviour.

H1: Health consciousness significantly impacts consumer’s attitude towards organic skin care products.

H2: Environmental consciousness significantly impacts consumer’s attitude towards organic skin care products.

H3: Appearance consciousness significantly impacts consumer’s attitude towards organic skin care products.

H4: Attitude towards organic skin care products significantly impacts purchase intention of an individual.

H5: Purchase intention of an individual significantly impacts their purchase behaviour towards organic skin care products.

H6: Past experience moderates the relationship between Purchase intention and purchase behaviour towards organic skin care products.

H7: Subjective norms moderates the relationship between Purchase intention and purchase behaviour towards organic skin care products.

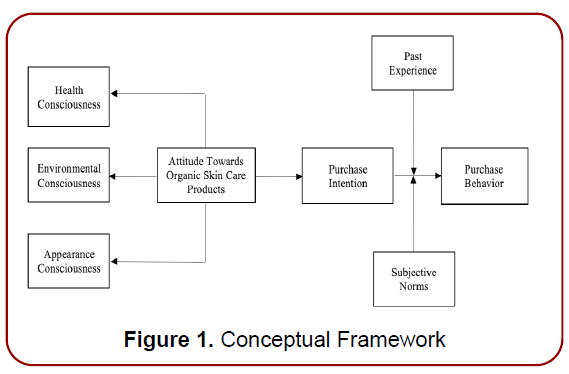

Based on the hypotheses mentioned, the study develops a framework as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework

Data Collection

The data collection methodology used in this study comprises a meticulously structured questionnaire that has been methodically prepared to measure various aspects of customer attitudes towards organic skin care products. A random sampling strategy has been carefully followed to assure the robustness and representativeness of the sample, corresponding with the specific criteria germane to the research objectives in this scholarly endeavour. In addition, a pilot study was carefully carried out to validate the efficacy of the questionnaire. This methodological decision demonstrates our dedication to data quality and the reliability of the study instrument. A dual-pronged approach involving online and offline mediums has been systematically performed to optimise respondent involvement and increase survey reach. The questionnaire link has been shared online, and physical copies have been dispersed in select shopping centres within the Delhi- NCR region. This thorough method resulted in a sizable dataset of 498 valid responses, showing a commendable response rate of roughly 83%. The data-gathering phase was systematically carried out across three months, beginning in July 2023 and concluding in September 2023, ensuring a comprehensive and temporally robust dataset for the analysis.

Measurement tools

All constructs are evaluated using several items on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 7 = ‘Strongly agree’). Health consciousness is measured using four questions developed [8]. Environmental consciousness is measured using a three-item scale created [9]. The statements of appearance consciousness are based on [10] three-item scale. Taylor & Todd’s (1995) study yielded a three-item customer attitude scale. The five statements [11] measure purchase intention. Buying behaviour is measured using four statements by [12]. Past experience and subjective norms are measured using four and three statements [13, 14]. Two marketing professors at a prestigious business school in New Delhi, India, agreed that the instrument’s content validity was enough for data collection [15]. In addition, 50 participants were examined using the internal consistency approach, i.e. Cronbach’s alpha [16]. For all measurement scales, the “Cronbach’s Alpha” value exceeded the suggested threshold of 0.7 [17]. These methods yielded satisfactory validation results for the data collection tools.

To investigate the presented hypothesis and framework, various analysis methodologies are applied. Psychometric attributes (reliability and validity of assessment tools), hypothesis testing, and the Hayes process approach were employed to address the study’s research problems. SPSS 25 and AMOS 22 are used to analyse the data. The statistical findings are discussed in greater detail below.

Validity and Reliability analysis of measurement

Key model statistics show that all endogenous variables are modelled simultaneously, with CMIN (ꭓ2) = 336.298, degree of freedom (df) = 181, and CMIN/df (ꭓ2/df) = 1.858, all of which are less than the criterion of 4 [18]. Goodness of fit (GFI=0.931, AGFI=0.912, IFI=0.971, NFI=0.939, CFI=0.971) and badness of fit indices (RMR=0.080, RMSEA=0.045, ECVI=1.031) are within range, indicating that the model has a good fit and psychometric properties can be interpreted. Cronbach’s alpha, which measures scale reliability, suggests that all items have an internal consistency of 0.8 or higher (Table 1).

| Descriptors | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Status | Paid Employment | 61 |

| Self-employed | 5 | |

| Retired | 7 | |

| Home-makers | 27 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 68 |

| Unmarried | 32 | |

| Age Group | 18-22 | 11 |

| 23-27 | 29 | |

| 28- 32 | 31 | |

| 33-37 | 13 | |

| 38-42 | 10 | |

| 42 and above | 6 | |

| Education | Senior Secondary | 3 |

| Graduate | 63 | |

| Post Graduate | 27 | |

| Other | 7 | |

| Prior Experience of organic skin care products | Yes | 91 |

| No | 9 | |

Table 1. Demographics

To establish validity, the average variance extracted (AVE), construct reliability (CR), and maximum shared variance (MSV) are utilised [19]. CR and AVE values must exceed the permitted limits of 0.7 and 0.5 for model convergent validity [20]. The MSV value for each dimension should be less than the AVE value for that dimension to show discriminant validity [21], indicating that all eight latent variables are distinct (Table 2). According to statistical values, all eight latent variables fully characterise their observed statements [22]. Table 3 depicts the constructwise measurement statements and their related factor loadings, the bulk of which are well within the permissible level (more than 0.5). Statements with factor loadings less than 0.5 have been “Deleted”.

| Mean | Std. Dev. | a | CR | AVE | HC | PI | PB | PE | AC | EC | SN | ATT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | 5.89 | 1.3 | 0.883 | 0.884 | 0.719 | 0.848 | |||||||

| PI | 5.5 | 1.39 | 0.912 | 0.913 | 0.677 | 0.16 | 0.823 | ||||||

| PB | 5.76 | 1.25 | 0.881 | 0.881 | 0.65 | 0.364 | 0.246 | 0.806 | |||||

| PE | 5.21 | 1.47 | 0.846 | 0.848 | 0.584 | 0.116 | 0.249 | 0.221 | 0.764 | ||||

| AC | 5.18 | 1.47 | 0.892 | 0.892 | 0.733 | 0.37 | 0.126 | 0.258 | 0.08 | 0.856 | |||

| EC | 5.78 | 1.6 | 0.864 | 0.866 | 0.683 | 0.243 | 0.204 | 0.243 | 0.124 | 0.267 | 0.826 | ||

| SN | 5.22 | 1.23 | 0.903 | 0.904 | 0.759 | 0.231 | 0.128 | 0.223 | 0.035 | 0.243 | -0.022 | 0.871 | |

| ATT | 5.63 | 1.3 | 0.872 | 0.873 | 0.697 | 0.361 | 0.203 | 0.297 | 0.124 | 0.325 | 0.332 | 0.165 | 0.835 |

Table 2. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

| Items | Statements | Factor loading |

|---|---|---|

| Health Consciousness | In general, I pay attention to my instincts concerning my health | 0.837 |

| I pay attention to how I feel physically during the day | 0.875 | |

| I think frequently about my health | 0.871 | |

| I am aware of any alterations in my health | Deleted | |

| Environmental Consciousness | When I consider how industries pollute the environment, I become dissatisfied and enraged |

0.86 |

| I believe consuming natural personal care products is really good for the environment | 0.886 | |

| The overall impression I receive from organic personal care products puts me in an environmentally conscious mentality | 0.834 | |

| Appearance Consciousness | My looks portray my personality | 0.864 |

| I must do everything in my power to always look my best | 0.881 | |

| Ageing will render me less appealing | 0.881 | |

| Attitude Towards Organic Skin Care Products | Buying organic cosmetics appeals to me | 0.86 |

| It’s an excellent idea to get organic cosmetics | 0.861 | |

| I have a favourable attitude toward purchasing organic cosmetics | 0.849 | |

| Purchase Intentions | The availability of up-to-date information assists me in making sound purchasing decisions | 0.862 |

| A wide selection of high-quality information assists me in making sound purchasing decisions | 0.87 | |

| In the future, I aim to purchase organic items | 0.865 | |

| I am continuously looking for additional organic products for my family’s requirements | 0.822 | |

| I plan to seek organic products, even if I have to go outside the city | 0.818 | |

| Purchase Behavior | I am a regular purchaser of organic products | 0.797 |

| Despite the availability of conventional alternatives, I continue to purchase organic items | 0.842 | |

| I don’t bother spending a higher price for organic things | 0.856 | |

| Prior to purchasing a product, I strive to learn about its environmental impact | 0.822 | |

| Past Experience | I’ve had a great experience with organic products | 0.816 |

| I am quite pleased with my use of organic items | 0.852 | |

| I bought and consumed a variety of organic items | 0.832 | |

| Because of its uniqueness, I bought and consumed organic products | 0.769 | |

| My close friends and family buys organic skin care products | 0.892 | |

| Subjective Norms | My loved ones expect me to purchase more organic skin care products for them | 0.91 |

| Many individuals have convinced me that I should buy organic items in order to live a healthier life | 0.9 |

Table 3. Factor Loadings

Hypotheses Result

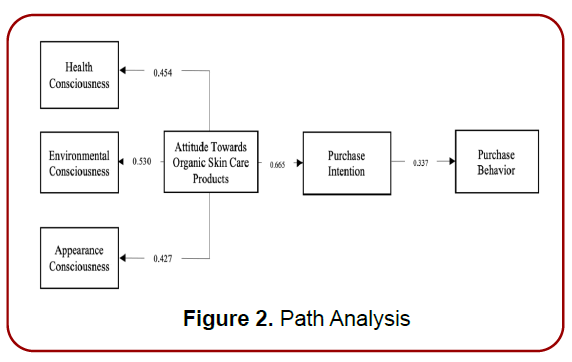

Path Analysis: A structural equation model (Table 4) is utilised for the analysis to validate the hypotheses. The present research conducts a comprehensive evaluation to determine the impact of customer attitude towards organic skin care products on purchase intention and eventually buying behaviour. Analysis shows a model fit: CMIN (ꭓ2)= 336.298, df=181, ꭓ2/df=1.858, goodness of fit indices (GFI=0.931, AGFI=0.912, NFI=0.939, CFI=0.971), badness of fit indices (RMR=0.080, RMSEA=0.045) which are also significant based on their standard values for acceptance (Hair et al., 2012).

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p-Value* | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Health Consciousnessà Attitude Towards Organic Skin Care Product | 0.454 | 0.045 | 10.088 | *** | Supported |

| H2 | Environmental Consciousness Attitude Towards Organic Skin Care Product | 0.53 | 0.041 | 12.926 | *** | Supported |

| H3 | Appearance Consciousnessà Attitude Towards Organic Skin Care Product | 0.427 | 0.033 | 12.939 | *** | Supported |

| H4 | Attitude Towards Organic Skin Care ProductàPurchase Intention | 0.665 | 0.056 | 11.875 | *** | Supported |

| H5 | Purchase Intentionà Buying Behavior | 0.337 | 0.041 | 8.219 | *** | Supported |

Table 4. Hypothesis Result

This research aims to identify the factors that shape customers’ purchase behaviour regarding organic skincare products. The research looks at various direct links between essential concepts. To begin, three hypotheses are tested to highlight the components of attitude formation towards organic skincare products. The first hypothesis investigates the association between health consciousness and attitudes towards organic skin care products, demonstrating a statistically significant (p<0.05) link with a significant regression weight (b=0.454) and CR value (10.088). Similarly, the second hypothesis investigates the association between environmental consciousness and attitudes towards organic skin care products, finding a significant relationship (p<0.05) with a significant regression weight (b=0.530) and CR value (12.926). The third hypothesis investigates the association between appearance consciousness and attitudes towards organic skin care products, revealing a significant (p<0.05) relationship with a significant regression weight (b=0.427) and CR value (12.939). As a result, three constructs– health consciousness, environmental consciousness, and appearance consciousness – emerge as precursors to creating attitudes towards organic skincare products.

The study then explores how customers’ attitudes towards organic skincare products influence their purchase intentions, which constitutes the fourth hypothesis. With a significant regression weight (b=0.665) and CR value (11.875), the study reveals a robust and significant (p<0.05) link between attitude formation and purchase intention. Finally, the fifth hypothesis investigates the direct relationship between purchase intention and actual purchasing behaviour to understand how intentions influence customer purchasing behaviours. This research demonstrates a statistically significant (p<0.05) link between purchase intention and purchasing behaviour, with a significant regression weight (b=0.337) and CR value (8.219). These findings add to a better understanding of the factors that influence customer behaviour in the organic skincare product market. All the statistical results are presented in Table 4 and diagrammatically in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Path Analysis

Moderation Analysis: The moderation analysis revealed in Table 5 that “Past Experience” had a strong and considerable role as a moderator in the link between “Purchase Intention” and “Purchasing Behaviour” for organic skincare products. The “Past Experience” (PE) coefficient is 0.9239, meaning that for every unit increase in past experience, there is a 0.9239 rise in purchase behaviour. This effect was statistically significant (p = 0.0000), emphasising the impact of people’s past experiences on their purchasing behaviour. Furthermore, the interaction term “Int_1” added complexity, which had a detrimental impact on purchasing behaviour. A unit increase in this term resulted in a 0.1466 drop in purchasing behaviour, which was statistically significant (p = 0.0000), illustrating the complex interplay between purchase intention and purchasing behaviour, especially in the presence of the moderator “Past Experience.” Overall, these results emphasise the importance of considering past experiences when analysing and predicting customer behaviour in the organic skincare product area.

| Coeff | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.6751 | 0.654 | 1.0323 | 0.3025 | -0.6104 | 1.9607 |

| PI | 0.8228 | 0.1262 | 6.5198 | 0 | 0.5747 | 1.0708 |

| PE | 0.9239 | 0.1485 | 6.2209 | 0 | 0.6319 | 1.2158 |

| Int_1 | -0.1466 | 0.0277 | -5.2922 | 0 | -0.2011 | -0.0922 |

Table 5. Moderation Analysis (Past Experience)

In contrast, the moderation analysis in Table 6 investigated the effect of “Subjective Norms” as a moderator in the similar link between “Purchase Intention” and “Buying Behaviour.” According to the findings, the moderating influence of “Subjective Norms” appeared to be rather restricted and statistically insignificant. Both “Purchase Intention” (PI) and “Past Experience” (PE) exhibited coefficients of 0.1595 and 0.1329, indicating minor influences on purchasing behaviour. However, neither of these effects was statistically significant (p > 0.05), implying that the presence of “Subjective Norms” may not have a substantial effect on the link between purchase intention and purchasing behaviour in the context of organic skincare products. The interaction term “Int_1” has a modest beneficial impact on purchasing behaviour, but this effect is not statistically significant (p = 0.7572), indicating that the moderating role of “Subjective Norms” may not be relevant in this specific consumer behaviour scenario. These findings imply that additional factors or modifiers may need to be investigated to better understand the dynamics of purchasing behaviour in this environment.

| Coeff | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3.8773 | 0.939 | 4.129 | 0 | 2.0315 | 5.7231 |

| PI | 0.1595 | 0.1708 | 0.9338 | 0.3509 | -0.1762 | 0.4952 |

| PE | 0.1329 | 0.1905 | 0.6975 | 0.4858 | -0.2415 | 0.5072 |

| Int_1 | 0.0106 | 0.0343 | 0.3093 | 0.7572 | -0.0568 | 0.078 |

Table 6. Moderation Analysis (Past Experience)

Marketers have been searching for answers to certain questions for a long time. Why does a consumer react in a certain way? What motivates them to buy? There is no simple answer to such questions. One needs to understand basic consumer behaviour factors [23]. The present research is an attempt in the same direction. The findings suggest that while buying organic skin care products, consumers’ attitude is formed by being health, environment and appearance conscious. These precursors act as motivating factors to develop the intention to buy organic skin care products. Once an intention is developed, a consumer is highly likely to buy the product. Furthermore, a consumer’s past experience can potentially change the final buying behaviour. The findings contribute to the existing body of research and have practical significance for organic skin care brands trying to improve customer relationships.

To identify the antecedents of consumers’ attitudes towards organic products (skincare), the statistical results came out with health consciousness (H1), environment consciousness (H2) and appearance consciousness (H3). All three results corroborate with the findings [24, 25]. Identifying these elements as important predictors of Indian women customers’ views towards organic skincare products demonstrates a multidimensional approach to consumer behaviour in this sector. For instance, Indian women have become more health-conscious [26]. With growing worries about the detrimental effects of artificial substances in skincare products, the desire for organic alternatives corresponds with the need for healthier, safer choices [27]. Second, in a nation where environmental pollution and waste management are becoming more evident, customers seek items that correspond with their environmental ideals [28]. Organic skincare products are frequently marketed as eco-friendly and sustainable, appealing to environmentally conscious consumers. Finally, the need to preserve and improve one’s physical attributes is firmly ingrained in Indian women, who are eager to invest in goods that promise to improve the appearance of their skin. Organic skincare products, frequently seen as natural and capable of producing apparent benefits, cater to this appearance-conscious clientele [29].

The statistical analysis provides evidence for a direct and significant relationship between attitude towards organic skin care products and purchase intention (H4). This finding is in congruence with [30]. Consumers’ preference for natural and risk-free ingredients, rising health and safety concerns in traditional skin care products, ethical and environmental issues, as well as trust in the effectiveness of organic skincare, all lead to positive attitudes and purchase intentions. Data analysis shows another positive association between purchase intention and consumers’ purchase behaviour towards organic skin care products (H5). Purchase intention [31] is a powerful predictor of purchase behaviour. When customers demonstrate a desire to purchase organic products (skincare), they are more likely to follow through. Emphasise [32] the relevance of perceived value and satisfaction in decisionmaking. Consumers with favourable intentions towards organic skincare products are inclined to be satisfied with their purchases, demonstrating the positive relationship between intention and behaviour.

Finally, the statistical evidence for past experience (H6) as a moderator between purchase intention and purchase behaviour gives a significant result. However, subjective norms (H7) fail to act as a moderator between the same relations. Past experience is a well-known influencer on purchasing behaviour because it forms buyers’ trust in their intentions. According to empirical studies such as [33], persons with favourable past experiences with a product are likelier to turn their intentions into real purchase behaviours. The inability of subjective norms to operate as a moderator in the same connection, on the other hand, may be linked to the intricate nature of consumer decisionmaking. While subjective norms or social pressures can impact purchase intentions [34, 35], their impact on purchasing behaviour is unclear. The present study gives statistical evidence of subjective norms not moderating the relation between intention and behaviour.

Theoretical Implications

The research findings contribute to the literature on consumer behaviour and marketing by providing insights that researchers and scholars can use in various ways [36-40]. This research adds to understanding the elements influencing customer attitudes towards organic skincare products. It adds complexity to the multidimensional [41- 52] consumer behaviour research approach by highlighting health, environmental, and appearance consciousness as major antecedents. Academics can use these findings to create more complete models and theories incorporating these dimensions in different consumer scenarios.

Furthermore, the positive relationship between customer attitudes and purchase intentions is consistent with earlier studies, demonstrating the strength of this relationship. Researchers can use the information to delve deeper into the factors underlying this association, such as the function of trust, product efficacy, and brand reputation. Furthermore, this link emphasises the need for marketing initiatives to improve consumer attitudes to drive purchase intentions ultimately. In addition, the study’s finding of a positive relationship between purchase intentions and actual purchasing behaviour confirms [53, 54] demonstration of the predictive ability of purchase intention. This discovery allows academicians to investigate this relationship in various consumer contexts and industries, adding to a better knowledge of consumer decision-making processes.

Finally, the study’s finding of experience as a strong moderator offers a more nuanced view of the function of trust and familiarity in customer behaviour. Researchers can expand on this by examining the conditions under which experience [55-61] influences buying behaviour and investigating its applicability in other product categories. On the other hand, the lack of support for subjective norms as a moderator underlines the need for greater investigation into the complicated nature of social impacts on consumer behaviour.

Managerial Implications

The study’s findings have important managerial implications for brands in the organic skincare product market [62]. Managers can use this knowledge strategically to increase consumer engagement and boost brand performance. To begin, marketers may effectively communicate the health advantages, eco-friendliness, and aesthetic upgrades of their products by aligning marketing tactics with the recognised antecedents [63] of consumer attitudes - health consciousness, environmental consciousness, and appearance consciousness. Transparent ingredient sources and comprehensive testing for safety and effectiveness can be critical in developing a favourable [64] customer perception. Furthermore, a concentrated effort to improve product information, such as ingredient sourcing, certifications, and environmental effects, allows consumers to make better choices. Using enticing marketing campaigns, special deals, product bundles, and loyalty programmes to capitalise on purchase intents can further boost consumer [65-71] involvement. Recognising the importance of past experiences, businesses should give high-quality products and great customer service constantly to drive repeat purchases and create loyalty. While subjective norms may not be significant modifiers, firms should remain aware of the nuances of social influences on purchasing intentions.