Zhu Mei 1,2 , Chenghui Yan 2 , Dan Liu 2 , Xiaolin Zhang 2 , Haixu Song 2 *, Yaling Han 2 *

1 College of Medicine and Biological Information Engineering, Northeastern University, Shenyang, Liaoning, 110167, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Frigid Zone Cardiovascular Diseases, Department of Cardiology and Cardiovascular Research Institute, General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, Shenyang, Liaoning Province, 110016, China.

* Correspondence: Yaling Han, State Key Laboratory of Frigid Zone Cardiovascular Diseases, Cardiovascular Research Institute and Department of Cardiology, General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, Wenhua Road 83, 110016 Shenyang, China. Email: hanyaling@163.net

Received: 14 May, 2025; Accepted: 16 June, 2025; Published: 24 June, 2025

Copyright: © 2025 Yaling Han and Haixu Song. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduc- tion in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

What is currently known about this topic?

Solid fuel use and i TyG index are established independent risk factors for Cardiometabolic Diseases (CMD) and multimorbidity (CMM).

What is the key research question?

Combined management of both solid fuel exposure and high level TyG index may nearly double this protective effect (91% risk reduction), highlighting the need for integrated prevention strategies.

What is new?

A synergistic effect between solid fuel and high TyG (CMM risk HR 2.06); 2) TyG mediates solid fuel’s effects on CMM (2.22%), diabetes (7.96%), and stroke (0.85%).

How might this study influence clinical practice?

Combined screening for air pollution and TyG effectively controls cardiometabolic disease development and multimorbidity.

Multimorbidity, the co-occurrence of two or more chronic diseases, has emerged as a critical global public health challenge amid aging populations1,2. Of particular concern is Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity (CMM), defined as the concurrent presence of Cardiovascular Metabolic Diseases (CMDs) such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes. CMM is associated with disproportionately higher mortality rates and healthcare costs compared to single diseases, with this burden escalating rapidly, especially in resource-limited settings3-5. These trends underscore the urgent need for effective interventions to mitigate CMD progression and alleviate individual and societal burdens. A key driver of CMD pathogenesis is Insulin Resistance (IR), a state of reduced tissue sensitivity to insulin that disrupts glucose homeostasis6-8. The Triglyceride-Glucose (TyG) index, a surrogate marker for IR, offers a convenient and reliable tool for early identification of metabolic dysregulation9,10. Accumulating evidence suggests that the TyG index not only predicts incident CMDs but also correlates with CMM risk11-13. However, its predictive utility is limited to mildto-moderate cardiovascular disease, failing to forecast severe cardiovascular events14,15. This limitation highlights the necessity of identifying complementary risk factors beyond metabolic dysfunction to optimize CMD prevention strategies16-18. Conventional research has predominantly examined isolated risk factors, either environmental exposures or biochemical markers, in relation to CMD/CMM19,20. Yet, complex chronic diseases typically arise from multifactorial interactions. Emerging data indicate that environmental pollutants and metabolic disturbances may synergistically exacerbate vascular injury, accelerating cardiovascular pathogenesis21,22. Despite these insights, the combined impact of environmental-metabolic interactions on CMD and CMM remains poorly characterized. Elucidating these synergistic mechanisms holds significant public health implications for developing targeted prevention approaches. Therefore, we aim to explore whether environmental risk factors and dyslipidemia/dysglycemia exacerbate the risk of CMD and CMM, as well as the mediating effect of TyG in the relationship between solid fuel use and CMD/CMM.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Data Source

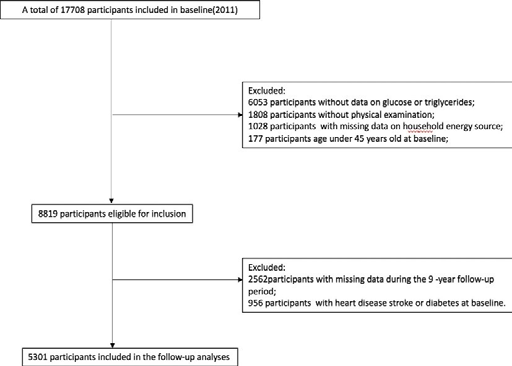

This study utilized data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a nationally representative, prospective cohort initiated in 2011–2012. CHARLS employs a multistage probability sampling strategy covering 150 counties/districts and 450 villages/ resident committees, encompassing approximately 10000 households (baseline response rate: 80.5%). Participants aged ≥45 years were followed biennially, with five completed survey waves to date (2011, 2013, 2015, 2018, and 2020). The study collects comprehensive data on demographics (age, sex, education, income), lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol use, physical activity), household air pollution exposures, and medical history23. All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Peking University Institutional Review Board (IRB00001052-11015). De-identified data are publicly accessible for research use. From the baseline cohort of 17708 participants, the inclusion criteria targeted middleaged and elderly adults aged 45 years and above. We excluded 6053 individuals lacking glucose or triglyceride measurements, 1808 without physical examination data, 1028 with missing household energy source information, and 177 aged <45 years at baseline. Additionally, we excluded 2562 participants lost to follow-up during the 9-year study period and 956 with pre-existing diagnoses of heart disease, stroke, or diabetes. After applying these exclusion criteria, the final analytical cohort comprised 5301 eligible participants (Figure 1)

Figure1.The flow chart of participant screen process.

All participants were asked: “Have you been diagnosed with [conditions listed below] by a doctor?” with each condition read individually. We defined “heart disease” as a positive response to “heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure, or other heart problems”; “stroke” as an affirmative answer to “stroke”; and “diabetes” as a positive response to “diabetes or high blood sugar”. Given our study population (aged ≥45 years), all diabetes cases were considered type 2 diabetes. Cardiometabolic disease (CMD) was defined as having at least one of these conditions (heart disease, stroke, or diabetes), while Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity (CMM) required concurrent presence of ≥2 conditions. The date of first reported diagnosis for each condition was recorded as the onset date.Definition Household Air Pollution from Solid Fuel

We classified household energy sources based on responses to two survey questions: “What is the main heating energy source?” and “What is the main source of cooking fuel?” Households reporting “Coal” or “Crop residue/Wood burning” for either question was categorized as solid fuel users. Those utilizing “Solar”, “Natural gas”, “Liquefied Petroleum Gas”, “Electric”, or “Other” were classified as clean fuel users. For analytical purposes, households were defined as solid fuel users if they reported using solid fuels for either heating or cooking at baseline.

Fasting blood samples were collected and analyzed by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention following standardized laboratory protocols. Serum triglycerides and glucose levels were measured using turbidimetric immunoassays, with coefficients of variation (CV) of 1.21% and 3.96%, respectively. The TyG index was calculated as: TyG = Ln [triglycerides (mg/dL) × glucose (mg/dL)/2]. Baseline covariates included,age (continuous), gender (male/female), body mass index (BMI= weight [kg]/height² [m], categorized as ≤24 or >24) ,education level (middle school or ≥middle school), marital status (“living with spouse” [married with spouse present] vs. “living without spouse” [all other statuses]), and residence (urban/rural), current drinking (yes/no) and smoking status (yes/no, defined as active smoking at time of survey).

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Based on previous literature, we stratified participants using the median TyG index value (8.56) as the cutoff (TyG 8.56 vs ≥8.56). Combined with solid fuel use, participants were further divided into four groups: (1) TyG ≤median & clean fuel; (2) TyG >median & clean fuel; (3) TyG ≤median & solid fuel; and (4) TyG >median & solid fuel. Continuous variables were compared using one-way ANOVA or Student’s t test, while categorical variables were analyzed using χ² or Fisher’s exact tests. We first examined baseline characteristics by TyG index levels and fuel types separately (Tables 1), followed by joint analysis of TyG index and solid fuel use (Table 1). Similarly, we initially assessed TyG index and solid fuel use as independent risk factors for CMD or CMM (Table 2). Using Cox proportional hazards models, we evaluated the associations of baseline TyG index and solid fuel use with incident heart disease, diabetes, and stroke from baseline (2011-2012) through 2020 follow-up, reporting hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (Table 2). Subsequent analyses focused on their joint effects on CMD and CMM (Table 2), and the stratified effects of solid fuel by TyG index levels (Figure 2). Three progressively adjusted models were constructed. Model 1 was unadjusted, Model 2 was adjusted by age (continuous), sex, Model 3 was adjusted by age (continuous), sex, BMI (continuous), education level (middle school vs ≥middle school), marital status (living with/without spouse), residence (urban/rural), drinking status (yes/no), and current smoking (yes/no). To explore potential mediation, we conducted mediation analyses considering elevated TyG index (≥8.56) as the mediator (M) between solid fuel use (X) and single CMD, CMD, or CMM (Y), using bootstrap resampling (500 iterations). To maximize statistical power, we only excluded participants with baseline prevalent disease for each specific outcome analysis (e.g., excluding only baseline CMM cases when analyzing CMM outcomes). Missing covariate data (n=5301 participants) were handled using multiple imputation with 10 imputed datasets. All analyses were performed using Stata (version 17, StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study participants according to TyG index and household fuel use

| Characteristics | Overall | TyG < Median & Clean fuel | TyG ≥ Median & Clean fuel | TyG < Median & Solid fuel | TyG ≥ Median & Solid fuel | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant, No. | 5301 | 640 (12.07) | 622 (11.7) | 2091 (39.5) | 1948 (36.8) | |

| Age, years, Mean ± SD | 58.19 ± 8.55 | 56.01 ± 8.33 | 56.39 ± 8.04 | 58.92 ± 8.73 | 58.70 ± 8.41 | < 0.001 |

| Gender, % — Male | 2413 (45.6) | 305 (47.7) | 264 (42.4) | 1062 (50.8) | 782 (40.2) | < 0.001 |

| Gender, % — Female | 2885 (54.4) | 334 (52.3) | 358 (57.6) | 1028 (49.2) | 1165 (59.8) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 23.29 ± 3.69 | 22.75 ± 3.58 | 24.67 ± 3.34 | 22.33 ± 3.44 | 24.07 ± 3.79 | < 0.001 |

| BMI < 24.0, n (%) | 3293 (62.1) | 435 (69.7) | 289 (45.3) | 1517 (74.6) | 1052 (52.5) | < 0.001 |

| Education level — < Middle school | 2008 (37.9) | 189 (30.3) | 374 (60.0) | 518 (25.4) | 1527 (75.0) | < 0.001 |

| Marital status — Live without spouse, n (%) | 730 (13.8) | 96 (15.4) | 94 (14.7) | 277 (13.6) | 263 (13.1) | 0.455 |

| Residence — Urban, n (%) | 572 (10.8) | 139 (22.3) | 151 (23.7) | 127 (6.2) | 155 (7.7) | < 0.001 |

| Drinking status — Yes, % | 1787 (33.7) | 229 (36.7) | 202 (31.7) | 741 (36.3) | 615 (30.7) | 0.001 |

| Currently smoking — Yes, % | 1616 (30.5) | 192 (30.8) | 167 (26.2) | 711 (35.0) | 546 (27.3) | < 0.001 |

| Notes | TyG index calculated as ln[triglycerides (mg/dL) × glucose (mg/dL) / 2]. Some small missing-data notes reported in the source. See original PDF for full footnotes. | |||||

| Outcome | Group (cases / person-years) | Model 1 HR (95% CI) | p | Model 2 HR (95% CI) | p | Model 3 HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMD | TyG < Median & Clean fuel (107 / 5435) | REF | - | REF | - | REF | - |

| TyG ≥ Median & Clean fuel (163 / 5466) | 1.52 (1.41–1.63) | < 0.001 | 1.50 (1.39–1.61) | < 0.001 | 1.49 (1.38–1.60) | < 0.001 | |

| TyG < Median & Solid fuel (458 / 17562) | 1.33 (1.25–1.41) | < 0.001 | 1.27 (1.19–1.35) | < 0.001 | 1.29 (1.22–1.38) | < 0.001 | |

| TyG ≥ Median & Solid fuel (647 / 16877) | 1.98 (1.86–2.10) | < 0.001 | 1.88 (1.77–2.00) | < 0.001 | 1.91 (1.80–2.04) | < 0.001 | |

| CMM | TyG < Median & Clean fuel (34 / 6195) | REF | - | REF | - | REF | - |

| TyG ≥ Median & Clean fuel (49 / 6544) | 1.37 (1.20–1.57) | < 0.001 | 1.33 (1.17–1.52) | < 0.001 | 1.16 (1.02–1.33) | 0.027 | |

| TyG < Median & Solid fuel (115 / 20390) | 1.04 (0.93–1.17) | 0.452 | 0.98 (0.87–1.10) | 0.162 | 1.02 (0.91–1.15) | 0.695 | |

| TyG ≥ Median & Solid fuel (288 / 21601) | 2.48 (2.23–2.75) | < 0.001 | 2.27 (2.04–2.53) | < 0.001 | 2.06 (1.85–2.29) | < 0.001 | |

| Model 1 = unadjusted; Model 2 = adjusted for age, gender; Model 3 = adjusted for age, gender, BMI, education, marital status, residence, drinking, smoking. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio. | |||||||

Table 2. Risk of cardiometabolic disease and multimorbidity upon coexposure stratified by the TyG index and household fuel use

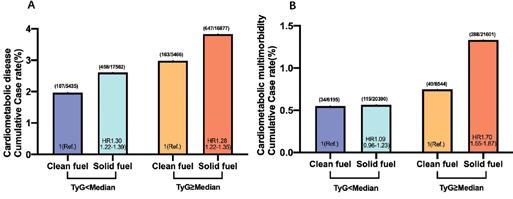

Figure 2. Association of household fuel use and cardiometabolic disease or multimorbidity according to TyG index.

Model 3 was adjusted for age, gender, TyG, index was calculated by ln[TC (mg/dl)×FBG (mg/dl)/2], BMI, education level, marital status, residence, drinking status, currently smoking status, HR, hazard ratio.

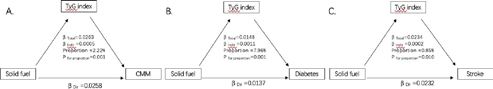

This study ultimately included 5301 participants with a mean age of 58.19±8.55 years, comprising 2413 males (45.5%). The majority of participants (76.2%, n=4039) reported solid fuel use (Table 1), while nearly half (48.5%, n=2570) exhibited elevated TyG index levels (≥median; Table 2). Stratification by both TyG index and fuel use revealed distinct demographic patterns: participants with lower TyG index and solid fuel use were oldest (58.92±8.73 years), while those with elevated TyG index using solid fuels showed the highest female predominance (59.8%, n=1165). Notably, the highest prevalence of overweight (BMI≥24) occurred in participants with elevated TyG index using clean fuels, whereas those with lower TyG index using solid fuels demonstrated the greatest proportions of individuals with less than middle school education (75.0%, n=1527), rural residence (93.8%, n=1908), and current smoking (35.0%, n=711). Alcohol consumption was most prevalent among participants with lower TyG index using clean fuels. With the longest follow-up time of 9 years, a total of 1375 (25.9%) participants had CMD and 486 (7.9%) participants had CMM, the incidence rates of CMM were 54.7 per 1000 years and the incidence rates of CMD were 45.3 per 1000 years. After adjusting for “age” “gender” “education levels” and so on demographic information, solely solid fuel using was independently associated with heart disease, stroke, diabetes, CMD, and CMM, similarly solely TyG index ≥ median was independently associated with heart disease, stroke, diabetes, CMD, and CMM (Table S3 and Table S5). During the 9-year follow-up period, we observed 1375 cases of CMD (25.9%; incidence rate 45.3 per 1000 person-years) and 486 cases of CMM (7.9%; incidence rate 54.7 per 1000 person-years). Multivariableadjusted analyses revealed that both solid fuel use and elevated TyG index (≥median) independently increased the risk of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, CMD, and CMM (Tables S3 and S5). When examining combined exposures, we found synergistic effects between environmental and metabolic risk factors. Compared to the reference group (TyG median with clean fuel use), the TyG≥ median with clean fuel group showed a 1.49-fold increased CMD risk (HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.38-1.60), while the TyG median with solid fuel group had a 1.29-fold elevated risk (HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.22-1.38). Most notably, participants with both risk factors (TyG≥ median using solid fuels) demonstrated the highest risk elevation for CMD (HR 1.91, 95% CI 1.80- 2.04) and CMM (HR 2.06, 95% CI 1.85-2.29) (Table 2). Single cardiovascular disease analyses revealed distinct patterns: for diabetes, elevated TyG index alone conferred a 2.17-fold risk increase (HR 2.17, 95% CI 1.94-2.41), with solid fuel use providing additional risk elevation (HR 2.47, 95% CI 2.33-2.83). Similarly, stroke risk was most pronounced in the combined exposure group (HR 1.93, 95% CI 1.74-2.14) compared to either exposure alone (Table S5). Stratification by TyG levels demonstrated that solid fuel effects varied by metabolic status. While solid fuel use increased CMD risk across all TyG levels, its impact on diabetes was only significant in the TyG≥ median stratum (HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.10-1.27). Notably, the joint exposure effect was particularly strong for CMM in the high TyG group (HR 1.70, 95% CI 1.55-1.87). Mediation analyses identified TyG index as a partial mediator between solid fuel exposure and cardiometabolic outcomes, accounting for 2.22% of the effect on CMM (P=0.001), 7.96% on diabetes (P=0.001), and 0.85% on stroke (P=0.010) (Figure 3). These findings suggest that while metabolic dysfunction contributes to the pathway, additional mechanisms likely underlie the environmental exposure-disease relationship.

Figure 3. Mediation effects of household fuel use to CMM, diabetes, and stroke by high level

A: TyG index mediates the effect of solid fuel use on CMM, B: TyG index mediates the effect of solid fuel use on diabetes, C: TyG index mediates the effect of solid fuel use on diabetes, TyG: index was calculated by ln[TC (mg/dl) × FBG (mg/dl)/2],CMM: Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity, Model 3 was adjusted for age, gender, BMI, education level, marital status, residence, drinking status, currently smoking status.

In this 9-year longitudinal study of 5301 middle-aged and older adults (≥45 years), we demonstrated that both solid fuel use and elevated TyG index (≥median) serve as23 independent risk factors for incident CMD and CMM. Notably, we identified a synergistic effect between these exposures, with coexposure to solid fuel use and high TyG index conferring the greatest risk for CMM development. Mediation analyses revealed that elevated TyG index partially mediated the association between solid fuel use and adverse cardiometabolic outcomes, particularly for CMM, diabetes, and stroke. Our findings align with accumulating evidence establishing the TyG index as a robust predictor of cardiometabolic risk. Originally proposed as a surrogate for insulin resistance [24], the TyG index has since been associated with increased cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients impaired cardiovascular function even in young, non-diabetic populations (OR 1.46 per 1-unit increase) [25], and elevated CMM risk (HR 1.54 per 1-unit increment) [11]. These observations collectively suggest that the TyG index captures early metabolic dysregulation preceding overt disease. The pathophysiological significance of the TyG index stems from its reflection of integrated glucose-lipid metabolism and insulin signaling pathways. Mechanistically, insulin resistance - quantified by the TyG index involves impaired activation of the PI3K-Akt and Ras/MAP kinase pathways downstream of insulin receptor binding [26]. This metabolic dysfunction represents a unifying feature linking diverse conditions including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and atherosclerosis [27,19]. Importantly, TyG index abnormalities often precede conventional diagnostic thresholds (e.g., HbA1c), as demonstrated by its correlation with coronary artery severity in normoglycemic individuals30.

Numerous epidemiological studies have established household solid fuel use as a significant independent risk factor for both CMD and CMM20, [31,32]. In developing regions where, modern clean energy remains inaccessible, solid fuels predominantly biomass (wood, crop residues, animal dung) and coal continue to serve as the primary energy source for cooking and heating, with an estimated 2.2 million tons combusted daily [33,34]. The substantial public health impact of this practice stems from the incomplete combustion process, which generates markedly higher concentrations of toxic emissions compared to clean energy sources, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, heavy metals, volatile organic compounds, and various particulate and gaseous pollutants [35,36]. These combustion byproducts exert detrimental health effects through multiple biological pathways, inducing intracellular damage, systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction all contributing to the development of hypertension, autonomic nervous system disorders, and other cardiometabolic condition [37, 39]. Particularly concerning is the formation of black carbon, which adsorbs numerous hazardous chemicals that interact synergistically with particulate matter to exacerbate cardiovascular and metabolic dysfunction [37,40]. The situation is especially alarming in rural communities, where our study found 89.2% of participants rely on solid fuels, often in poorly ventilated indoor environments where pollutant concentrations reach 2-5 times outdoor levels. Middle-aged and elderly populations face disproportionate risks due to prolonged indoor exposure coupled with declining physiological resilience. Our findings demonstrate that transitioning this vulnerable demographic away from solid fuel use could substantially reduce CMD incidence and prevent progression from single to multiple cardiometabolic conditions, representing a crucial intervention point for improving population health outcomes. TyG index, a well-established surrogate marker for insulin resistance, has been consistently associated with increased risks of both CMD and CMM12,13. Emerging evidence suggests that when combined with inflammatory markers like high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), the TyG index demonstrates synergistic effects on CMM risk [41]. However, the potential interaction between indoor environmental pollutants and metabolic dysregulation, as reflected by the TyG index, remains unexplored in relation to cardiovascular metabolic outcomes. Environmental pollutants are known to trigger pathological processes through multiple mechanisms, including the stimulation of neutrophil extracellular traps that contribute to atherosclerotic development [22]. Current research on solid fuel use and CMD/CMM primarily focuses on healthy populations, potentially underestimating the complex interplay between environmental and metabolic risk factors [42]. Our study addresses this gap by examining the combined effects of solid fuel exposure (as an environmental risk indicator) and elevated TyG index (as a metabolic dysregulation marker) on cardiometabolic health [19,20]. The findings reveal that while either risk factor alone significantly increases CMD risk, their coexistence produces a compounded effect. Specifically, concurrent exposure to solid fuels and high TyG levels doubles the prevalence of CMM compared to elevated TyG alone. This synergistic relationship may be explained through several biological pathways: the TyG index reflects underlying glucose and lipid metabolism disorders that create a pro-inflammatory state, while environmental pollutants entering this compromised metabolic environment may exacerbate cellular damage and cardiovascular dysfunction. Supporting this notion, recent studies have demonstrated that air pollutants can influence metabolic parameters through epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation patterns that affect the TyG index [43]. Our mediation analysis further elucidates these relationships, identifying the TyG index as a partial mediator between solid fuel exposure and adverse outcomes, particularly for CMM, diabetes, and stroke. Although the mediation proportions were modest (ranging from 0.85% to 7.96%), these findings suggest that metabolic dysfunction represents one pathway through which environmental exposures exert their cardiometabolic effects. The clinical and public health implications of these findings are substantial, particularly in aging populations where multimorbidity prevalence is rising dramatically [44,45]. The economic burden is equally concerning, with studies showing that progression from one to two chronic conditions increases out-of-pocket health expenditures by 5.2-fold, and this escalates to 10.1- fold when progressing from two to three conditions. Our results demonstrate that comprehensive interventions addressing both environmental and metabolic risk factors could potentially reduce disease risk by 0.91-fold for CMD and 1.06-fold for CMM, representing substantially greater protection than targeting either factor alone (Table 2). Practical interventions might like, promoting clean energy adoption and improving ventilation systems, enhancing community-based screening for metabolic abnormalities, implementing early intervention programs for individuals with elevated TyG indices, developing integrated prevention strategies that address both environmental and metabolic risk factors.

While this study benefits from its nationally representative prospective design, several limitations warrant consideration. The predominantly rural sample may limit generalizability, and self-reported exposure and outcome data introduce potential recall bias. Furthermore, the TyG index represents only one aspect of metabolic dysfunction, and additional biomarkers could provide more comprehensive insights. Future research should incorporate longer follow-up periods and objective measures of exposure and outcomes to validate these findings.

The partial mediation by TyG index offers insights into potential biological mechanisms while highlighting the need for further investigation into additional pathways linking environmental exposures to cardiometabolic outcomes. In conclusion, our study provides compelling evidence that the interaction between indoor environmental pollution and metabolic dysregulation significantly amplifies cardiometabolic risk. These findings underscore the importance of multidimensional prevention strategies that simultaneously address environmental and metabolic determinants of health, particularly in vulnerable aging populations.

CMM: Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity; CMDs: cardiovascular metabolic diseases; IR: insulin resistance; TyG index: triglyceride glucose index; CHARLS: China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study; CV: coefficients of variation; BMI: Body mass index; SD: standard deviation; ANOVA: analysis of variance; HR: Hazard Ratio; OR: odds ratio; PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; Akt: protein kinase B; Ras/MAP: RAS-Mitogen-Activated Protein; hsCRP: C-reactive protein; HbA1c: Glycated Haemoglobin A1c; DNA: Deoxyribo Nucleic Acid.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Peking University Institutional Review Board (IRB00001052-11015).

Consent for Publication

Not applicable

Availability of Data and Materials

The research data of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author under reasonable circumstances.

Competing Interests

All authors participated declared that they had no anything to disclose regarding funding or conflict of interest with respect to present study.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82470303,82270493).

Author Contributions

YH conceptualized the study; CH and HS conceived and designed research; ZM and analyzed data; ZM drafted the manuscript; DL and XZ revised the manuscript; HS supervised the project; YH provided funding. All authors contributed with productive discussions and knowledge to the final version of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study used data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) database. We are very grateful to the CHARLS research team for their hard work.

1. Fortin, Martin, Jeannie Haggerty, José Almirall, Tarek Bouhali, Maxime Sasseville, and Martin Lemieux. “Lifestyle factors and multimorbidity: a cross sectional study.” BMC public health 14 (2014): 1-8.

2. Chowdhury, Saifur Rahman, Dipak Chandra Das, Tachlima Chowdhury Sunna, Joseph Beyene, and Ahmed Hossain. “Global and regional prevalence of multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis`.” EClinicalMedicine 57 (2023).

3. Barnett, Karen, Stewart W. Mercer, Michael Norbury, Graham Watt, Sally Wyke, and Bruce Guthrie. “Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study.” The Lancet 380, no. 9836 (2012): 37-43.

4. Lei, Lubi, Jingkuo Li, and Bin Wang. “Efficacy and Safety Profile of Berberine Treatment in Improving Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized, Double- blind Trials.” Cardiology Discovery 3, no. 02 (2023): 112-121.

5. Han, Yuting, Yizhen Hu, Canqing Yu, Yu Guo, Pei Pei, Ling Yang, Yiping Chen et al. “Lifestyle, cardiometabolic disease, and multimorbidity in a prospective Chinese study.” European heart journal 42, no. 34 (2021): 3374-3384.

6. Hill, Michael A., Yan Yang, Liping Zhang, Zhe Sun, Guanghong Jia, Alan R. Parrish, and James R. Sowers. “Insulin resistance, cardiovascular stiffening and cardiovascular disease.” Metabolism 119 (2021): 154766.

7. Abdul-Ghani, Muhammad, Pietro Maffei, and Ralph Anthony DeFronzo. “Managing insulin resistance: the forgotten pathophysiological component of type 2 diabetes.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 12, no. 9 (2024): 674-680.

8. Kernan, W. N., S. E. Inzucchi, C. M. Viscoli, L. M. Brass, D. M. Bravata, and R. I. Horwitz. “Insulin resistance and risk for stroke.” Neurology 59, no. 6 (2002): 809-815.

9. Yang, Ying, Xiangting Huang, Yuge Wang, Lin Leng, Jiapei Xu, Lei Feng, Shixie Jiang et al. “The impact of triglyceride-glucose index on ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Cardiovascular diabetology 22, no. 1 (2023): 2.

10. Tahapary, Dicky Levenus, Livy Bonita Pratisthita, Nissha Audina Fitri, Cicilia Marcella, Syahidatul Wafa, Farid Kurniawan, Aulia Rizka et al. “Challenges in the diagnosis of insulin resistance: focusing on the role of HOMA-IR and Tryglyceride/glucose index.” Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 16, no. 8 (2022): 102581.

11. Zhang, Qin, Shucai Xiao, Xiaojuan Jiao, and Yunfeng Shen. “The triglyceride-glucose index is a predictor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in CVD patients with diabetes or pre-diabetes: evidence from NHANES 2001–2018.” Cardiovascular diabetology 22, no. 1 (2023): 279.

12. Zhang, Zenglei, Lin Zhao, Yiting Lu, Xu Meng, and Xianliang Zhou. “Relationship of triglyceride-glucose index with cardiometabolic multi-morbidity in China: evidence from a national survey.” Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome 15, no. 1 (2023): 226.

13. Xiao, Danrui, Honglin Sun, Long Chen, Xiang Li, Huanhuan Huo, Guo Zhou, Min Zhang, and Ben He. “Assessment of six surrogate insulin resistance indexes for predicting cardiometabolic multimorbidity incidence in Chinese middle◻aged and older populations: Insights from the China health and retirement longitudinal study.” Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews 40, no. 1 (2024): e3764.

14. Quist, Sara W., Alexander V. van Schoonhoven, Stephan JL Bakker, Michał Pochopień, Maarten J. Postma, Jeanni MT van Loon, and Jeroen HJ Paulissen. “Cost-effectiveness of finerenone in chronic kidney disease associated with type 2 diabetes in The Netherlands.” Cardiovascular Diabetology 22, no. 1 (2023): 328.

15. Tao, Li-Chan, Jia-ni Xu, Ting-ting Wang, Fei Hua, and Jian-Jun Li. “Triglyceride-glucose index as a marker in cardiovascular diseases: landscape and limitations.” Cardiovascular diabetology 21, no. 1 (2022): 68.

16. Cohen, Aaron J., Michael Brauer, Richard Burnett, H. Ross Anderson, Joseph Frostad, Kara Estep, Kalpana Balakrishnan et al. “Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015.” The lancet 389, no. 10082 (2017): 1907-1918.

17. Gordon, Stephen B., Nigel G. Bruce, Jonathan Grigg, Patricia L. Hibberd, Om P. Kurmi, Kin-bong Hubert Lam, Kevin Mortimer et al. “Respiratory risks from household air pollution in low and middle income countries.” The lancet Respiratory medicine 2, no. 10 (2014): 823-860.

18. Yu, Kuai, Gaokun Qiu, Ka-Hung Chan, Kin-Bong Hubert Lam, Om P. Kurmi, Derrick A. Bennett, Canqing Yu et al. “Association of solid fuel use with risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in rural China.” Jama 319, no. 13 (2018): 1351-1361.

19. Chen, Wei, Xiaoyu Wang, Jing Chen, Chao You, Lu Ma, Wei Zhang, and Dong Li. “Household air pollution, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and risk of cardiometabolic multimorbidity: results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study.” Science of The Total Environment 855 (2023): 158896.

20. Zhen, Shihan, Qian Li, Jian Liao, Bin Zhu, and Fengchao Liang. “Associations between Household Solid Fuel Use, Obesity, and Cardiometabolic Health in China: A Cohort Study from 2011 to 2018.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4 (2023): 2826.

21. Yan, Chunyu, Guang Chen, Yingyu Jing, Qi Ruan, and Ping Liu. “Association between air pollution and cardiovascular disease risk in middle-aged and elderly individuals with diabetes: inflammatory lipid ratio accelerate this progression.” Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome 17, no. 1 (2025): 65.

22. Zhu, Yutong, Hongbing Xu, Tong Wang, Yunfei Xie, Lingyan Liu, Xinghou He, Changjie Liu et al. “Pro- inflammation and pro-atherosclerotic responses to short-term air pollution exposure associated with alterations in sphingolipid ceramides and neutrophil extracellular traps.” Environmental Pollution 335 (2023): 122301.

23. Zhao, Yaohui, Yisong Hu, James P. Smith, John Strauss, and Gonghuan Yang. “Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS).” International journal of epidemiology 43, no. 1 (2014): 61-68.

24. Simental-Mendía, Luis E., Martha Rodríguez-Morán, and Fernando Guerrero-Romero. “The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects.” Metabolic syndrome and related disorders 6, no. 4 (2008): 299-304.

25. Guo, Dachuan, Zhenguo Wu, Fei Xue, Sha Chen, Xiangzhen Ran, Cheng Zhang, and Jianmin Yang. “Association between the triglyceride-glucose index and impaired cardiovascular fitness in non-diabetic young population.” Cardiovascular Diabetology 23, no. 1 (2024): 39.

26. Saltiel, Alan R. “Insulin signaling in health and disease.” The Journal of clinical investigation 131, no. 1 (2021).

27. Czech, Michael P. “Insulin action and resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes.” Nature medicine 23, no. 7 (2017): 804-814.

28. Samuel, Varman T., and Gerald I. Shulman. “Mechanisms for insulin resistance: common threads and missing links.” Cell 148, no. 5 (2012): 852-871.

29. Zhao, Sheng, Zuoxiang Wang, Ping Qing, Minghui Li, Qingrong Liu, Xuejie Pang, Keke Wang, Xiaojin Gao, Jie Zhao, and Yongjian Wu. “Comprehensive analysis of the association between triglyceride-glucose index and coronary artery disease severity across different glucose metabolism states: A large-scale cross- sectional study from an Asian cohort.” Cardiovascular Diabetology 23, no. 1 (2024): 251.

30. Liu, Yang, Ning Ning, Ting Sun, Hongcai Guan, Zuyun Liu, Wanshui Yang, and Yanan Ma. “Association between solid fuel use and nonfatal cardiovascular disease among middle-aged and older adults: findings from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS).” Science of The Total Environment 856 (2023): 159035.

31. Ji, Haoqiang, Qian Chen, Ruiheng Wu, Jia Xu, Xu Chen, Liang Du, Yunting Chen et al. “Indoor solid fuel use for cooking and the risk of incidental non- fatal cardiovascular disease among middle-aged and elderly Chinese adults: a prospective cohort study.” BMJ open 12, no. 5 (2022): e054170.

32. Barnes, Douglas F., Keith Openshaw, Kirk R. Smith, and Robert Van der Plas. “What makes people cook with improved biomass stoves.” World Bank technical paper 242 (1994): 2004.

33. Kumar, Raj, Jitendra K. Nagar, Neelima Raj, Pawan Kumar, Alka S. Kushwah, Mahesh Meena, and S. N. Gaur. “Impact of domestic air pollution from cooking fuel on respiratory allergies in children in India.” Asian Pacific Journal of Allergy and Immunology 26, no. 4 (2008): 213.

34. Chen, Rui, Bin Hu, Ying Liu, Jianxun Xu, Guosheng Yang, Diandou Xu, and Chunying Chen. “Beyond PM2. 5: The role of ultrafine particles on adverse health effects of air pollution.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects 1860, no. 12 (2016): 2844- 2855.

35. Ni, Kun, Ellison Carter, James J. Schauer, Majid Ezzati, Yuanxun Zhang, Hongjiang Niu, Alexandra M. Lai et al. “Seasonal variation in outdoor, indoor, and personal air pollution exposures of women using wood stoves in the Tibetan Plateau: Baseline assessment for an energy intervention study.” Environment international 94 (2016): 449-457.

36. Deng, Yan, Qian Gao, Dan Yang, Hui Hua, Nan Wang, Fengrong Ou, Ruxi Liu, Bo Wu, and Yang Liu. “Association between biomass fuel use and risk of hypertension among Chinese older people: a cohort study.” Environment International 138 (2020): 105620.

37. Garshick, Eric, Stephanie T. Grady, Jaime E. Hart, Brent A. Coull, Joel D. Schwartz, Francine Laden, Marilyn L. Moy, and Petros Koutrakis. “Indoor black carbon and biomarkers of systemic inflammation and endothelial activation in COPD patients.” Environmental research 165 (2018): 358-364.

38. 38. Li, Wenyuan, Elissa H. Wilker, Kirsten S. Dorans, Mary B. Rice, Joel Schwartz, Brent A. Coull, Petros Koutrakis et al. “Short◻term exposure to air pollution and biomarkers of oxidative stress: the Framingham Heart Study.” Journal of the American Heart Association 5, no. 5 (2016): e002742.

39. Zanobetti, Antonella, Heike Luttmann-Gibson, Edward S. Horton, Allison Cohen, Brent A. Coull, Barbara Hoffmann, Joel D. Schwartz et al. “Brachial artery responses to ambient pollution, temperature, and humidity in people with type 2 diabetes: a repeated- measures study.” Environmental health perspectives 122, no. 3 (2014): 242-248.

40. Cui, Cancan, Lin Liu, Yitian Qi, Ning Han, Haikun Xu, Zhijia Wang, Xinyun Shang et al. “Joint association of TyG index and high sensitivity C-reactive protein with cardiovascular disease: a national cohort study.” Cardiovascular Diabetology 23, no. 1 (2024): 156.

41. Huang, Shengbing, Chunmei Guo, Ranran Qie, Minghui Han, Xiaoyan Wu, Yanyan Zhang, Xingjin Yang et al. “Solid fuel use and cardiovascular events: A systematic review and meta◻analysis of observational studies.” Indoor Air 31, no. 6 (2021): 1722-1732.

42. Zhang, Ke, Gongbo Chen, Jie He, Zhongyang Chen, Mengnan Pan, Jiahui Tong, Feifei Liu, and Hao Xiang. “DNA methylation mediates the effects of PM2. 5 and O3 on ceramide metabolism: A novel mechanistic link between air pollution and insulin resistance.” Journal of Hazardous Materials 469 (2024): 133864.

43. Hou, Xuhong, Peizhu Chen, Gang Hu, Yue Chen, Siyu Chen, Jingzhu Wu, Xiaojing Ma et al. “Distribution and related factors of cardiometabolic disease stage based on body mass index level in Chinese adults-The National Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders Survey.” Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews 34, no. 2 (2018): e2963.

44. Glynn, Liam G. “Multimorbidity: another key issue for cardiovascular medicine.” The Lancet 374, no. 9699 (2009): 1421-1422.

45. Meng, Qingyue, Hai Fang, Xiaoyun Liu, Beibei Yuan, and Jin Xu. “Consolidating the social health insurance schemes in China: towards an equitable and efficient health system.” The Lancet 386, no. 10002 (2015): 1484-1492.