Barudin Fozi1*, Rudwan Yasin2, Dawit Abdi3*, Olifan Getachew1

1School of Medicine, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia

2Department of Anesthesia, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia

3Department of psychiatry, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia *

Correspondence: Barudin Fozi, School of Medicine, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia, E-mail: yasinredwan5@ gmail.com

Dawit Abdi, Department of psychiatry, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia E-mail: dawitabdibeka@gmail.com

Copyright: © 2025 Fozi B and Abdi D. This is an open-ac- cess article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Objectives: Postoperative pain continues to be a serious consequence of surgical intervention. However, factors may contribute to the development of postoperative pain; these could be preoperative factors, intra-operative and postoperative factors are realized to cause enhancement of postoperative pain. Therefore, in this study to identify the problem and its factors.

The aim of this study to assess the magnitude and factor associated with postoperative pain among elective surgery patient at Arsi University Asella teaching and referral hospital from July 1-2023 to October 30 2023.

Methods: Institutional based cross-sectional study was conducted and 290 patients included postoperative patients from surgical ward of Asella teaching and referral hospital from July 1-2023 to October 30, 2023. The data were collected using chart review; Consecutive sampling technique was used to recruit study participants. A numerical rating scale (NRS-11) was used for the assessment of pain. Data analysis was done using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS).

25. Descriptive statistics, bivariate, and multivariable logistic regression was used. An adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval was used to determine the association. A p-value of less than 0.05 was used to declare statistical significance.

Results: A two hundred ninety patient were participated in the study with a response rate of 100%.the magnitude of postoperative pain was 67%, 71%, and 75.5% at 2 hr,6hr, and 12 hr., respectively. On bi-variable analysis, The age ≥60 years patients POP surgery were 1.34 times more likely to have moderate to severe postoperative pain than those young adult

patients who had age between 18- 45 years (AOR=1.34, 95% CI=1.15,3.94). Similarly, the odds of having moderate to severe postoperative pain were 1.96 times [AOR: 1.96, 95%CI: (1.90, 4.11)] higher among participants who had incision length of > 10 cm than those with incision length of < 10 cm. were identified as associated factor of postoperative moderate to severe pain after surgery.

Conclusion: The study confirmed that the magnitude of postoperative pain was high 219 patients were complaining POP moderate- severe postoperative pain after surgery 75% which needs the attention of health professionals working on surgical patients and considering factors associated with post-operative pain.

Keywords: Postoperative pain; Associated Fac- tors; Magnitudes

Surgical interventions are common medical proce- dures performed to treat various conditions and im- prove patient health. While surgery aims to restore or enhance well-being, the postoperative period often brings about challenges, with postoperative pain be- ing a prominent concern. Postoperative pain is a com- plex and subjective experience that can significantly impact the recovery and overall satisfaction of adult elective surgical patients [1].

Pain is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional expe- rience associated with actual or potential tissue dam- age as defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP)”. In all contexts of health- care services, it is one of the most prevalent medical and surgical problems. It is becoming more widely ac- knowledged that pain is a very subjective and individ- ualized experience that is influenced by a variety of factors, including mood, life events, fear, anxiety, and anticipation. The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified pain as a worldwide issue and Pain re- lief has been acknowledged as a human right [2-4].

Understanding the factors associated with postoper- ative pain is essential for healthcare providers to de- velop targeted and evidence-based pain management strategies. Patient-related factors, such as age, gen- der, pre-existing medical conditions, and psychologi- cal factors, may influence the perception and intensity of postoperative pain. Additionally, the type and com- plexity of surgical procedures, as well as variations in analgesic regimens and perioperative care protocols, contribute to the variability in postoperative pain expe- riences [5].

Controlling acute pain after surgery is important not only in the immediate postoperative phase, but also to prevent chronic postsurgical pain, which can develop in as many as 10% of patients [4]. Effective postop- erative pain control is an essential component of the care of surgical patients. Advances in pharmacology, techniques, and education are making major inroads into the management of postoperative pain [6].

Post operation pain intensity is associated with vari- ables like patient age, sex, type of surgery, anesthe-

sia, duration of surgery and previous painful experi- ence of the patient are some of the factors associated with moderate to severe postoperative pain develop- ment [7]. Adequate postoperative pain management is essential to keep patients comfortable, help them to quickly recover, and prevent postoperative com- plications. Substantial evidence has been generated over the last decade, suggesting that severe acute pain after surgery may progress to the development of chronic pain [8].

The advantages of effective postoperative pain man- agement include patient comfort and satisfaction, ear- lier mobilization, fewer pulmonary and cardiac compli- cations, reduced risk of deep vein thrombosis, faster recovery with less likelihood of the development of neuropathic pain, and reduced cost of care [6]. De- spite improved understanding of pain mechanisms, in- creased awareness of the prevalence of postsurgical pain, advances in pain-management approaches, and other focused initiatives aimed at improving pain-re- lated outcomes in recent decades, inadequately controlled postoperative pain continues to be a wide- spread, unresolved healthcare problem. Most surgical patients spend their immediate postoperative period in the PACU, where pain management, being unsat- isfactory and requiring improvements, and affects fur- ther recovery.

Pain is defined as “an unpleasant sensory and emo- tional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such dam- age”. Postoperative pain is usually related to tissue injury during surgical procedures like skin incision, tis- sue dissection, manipulation and traction. Such pain is usually acute and it serves an important factor to alert the body of potential or actual tissue injury and inflammatory responses [9].

Postoperative pain remains a common problem among surgical patients and it’s difficult to make a global evaluation of the magnitude of POP as the fig- ures vary depending on the methods being used. Evi- dence indicates that in the United States, over 80% of postoperative pain is not adequately addressed [1]. A postoperative patient who is experiencing pain cannot ambulate, therefore, may develop deep vein throm- bosis. Again, a patient who is experiencing chest pain may have suppressed of the cough reflex, therefore develop lung infection [10].

The consequences of ineffective pain management extend beyond immediate discomfort, affecting pa- tients’ functional capabilities, quality of life, and overall healthcare costs. Prolonged duration of opioid use, delayed recovery, and increased morbidity and mor- tality risks are among the potential outcomes of sub-

Age, incision site and incision length were the independent associated factors for the experience of postoperative pain.

optimal postoperative pain management [11].

Postoperative pain remains one of the major chal- lenges in the care of surgical patients. Although care has improved, studies show that postoperative pain continues to be inadequately treated and patients still suffer moderate to severe pain during & after surgery [7]. Possible post-surgical management and treat- ment options include multimodal analgesia involving opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory, paracetamol, regional block and other adjuvants depending on the severity of pain.

This study was conducted in Arsi University Asella Teaching and Referral Hospital which is located in Assela town, south east Ethiopia, Arsi Zone which is 175Km South of Addis Ababa. The town is located at a latitude and longitude of 7057 I N/3907I E respectively with an elevation of 2430 m, is characterized by mild sub-tropical weather with the maximum and minimum temperatures of 18°c and 5°c respectively. Based on an Asella town health office annual report in 2011, it had an estimated total population of 97652 of which 49104 (50.3%) were males and 48548 (49.7%) were females.

Arsi University ARTH has a broad category of special- ties including; Internal Medicine, General Surgery, Gy- necology and Obstetrics, and Pediatric. Orthopedics, Neurosurgery, Urology, Maxillofacial, Plastic Surgery, Ophthalmology, and Anesthesiology are other special- ties serving the hospital. It has a total of 297 beds, 50 in surgical and 46 in gynecology and obstetrics units specifically. The study period was from July 1 to Octo- ber 30 2023G.C at ARTH.

Ethical considerationPrior to the study, ethical clearance was obtained from the Departmental Research and Ethics Review Com- mittee (DRERC) of College of Health Sciences of Arsi University and the acceptance was also obtained from the study institutions (Arsi teaching hospital). More- over, full clarification about the purpose of the study was made to the Authorized person of the health facil- ity. The purpose of the study was explained to the pa- tients who were included in the study. Verbal informed consent from the patients was asked and Confiden- tiality of the information was assured by using code numbers and keeping questionnaires locked and pa- tients who were in pain during this study period were treated by their care giver, who are informed by data collector.

Study design and populationInstitutional based Cross-sectional study design was employed, the sources of population were adult pa- tients who underwent various elective surgeries in the study period in ATRH. Study population were All adult elective surgery patients who were selected to under- went elective surgery operation in Asella Teaching and Referral Hospital

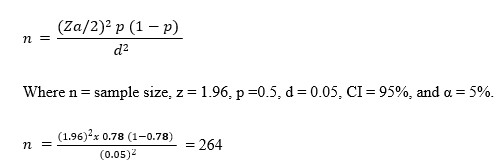

Size determinationThe sample size required for this study was obtained by using single proportion formula where the initial sample size was obtained, by considering a 5% de- gree of precision (d). The magnitude was taken from a previous study; the magnitude of POP was 78% [7]. Sample size was determined using the finite popula- tion correction formula by assuming the proportion as 0.5and 5% margin of error at the 95% confidence in- terval using the following formula:

We added 10% of nf for the non-response rate (i.e., NF=264 × 10%=264 + 26.4=290.4,). Therefore, total sample sizes of patients were 290.

All consecutive patients who fulfilled the inclusion crite- ria were collected until the sample sized was reached

Data collection Instruments and proceduresData were collected using chart review by questioner and checklist. The numeric rating scale was used to assess the level of pain. The numeric rating scale was translated into the Oromo and Amharic language. The checklist was used to extract data on the type of sur- gery, anesthesia, a drug used for intraoperative and postoperative pain management, and duration of sur- gery and anesthesia from the patients’ charts and an- esthetic record sheets. The supervisor was controlling the data quality and its completeness at the end of data collection for a single participant.

Data quality controlTo assure the data quality a one-day standardized training was given to one supervisor and four data col- lectors. Appropriate information and instruction were given to the objective, relevance of the study, confi- dentiality of information, respondent’s rights, and tech- nique of data collection. A pre-test was conducted in another hospital with 5% of the total sample size and the questions were checked for clarity, completeness, consistency and the quality of the data collected was checked on a daily basis by supervisors and principal investigators.

Data processing and analysisThe data was entered on Epi-data software version 4.62 and were transferred to SPSS version 25 com- puter program for analysis. Descriptive statistics was used to summarize data, tables and figures for display results. The association among independent factors and the outcome variable were determined by chi- squared test, bi-variable and multivariable logistic re- gression. The statistical significance was P <0.2 for bi-variable and <0.05 for multivariable regression. Crude and Adjusted Odds Ratio were used to see the strength of the association for bi-variable and multi- variable logistic regression respectively. P-value of

less than 0.05 was considered as statistically signifi- cant. The model fitness test was checked by Hosmer and lameshows goodness of fit test.

Operational definitionsPostoperative pain: The presence of pain in the postoperative period was defined as a patient having pain and any pain score other than zero starting im- mediately after surgery and recovery room.

Numerical pain rating scale (NRS): is a valid method of pain assessment where patients are asked to score their pain ratings on a scale of 0–10, corresponding to current, best, and worst pain experienced over the 12 hours (38).

Severe post-operative pain: a pain rating of 7-10 in 11-point numerical pain rating scale.

Moderate post-operative pain: a pain rating of 4-6 in 11-point numerical pain rating scale.

Mild post-operative pain: a pain rating of 1-3 in 11-point numerical pain rating scale.

No pain: a pain rating of 0 (Zero) in 11-point numerical pain rating scale.

Recovery room: is a space a patient is taken to after surgery to safely regain consciousness from anesthe- sia and receive appropriate postoperative care.

Moderate to severe pain: numeric rating score of moderate to severe post-operative pain.

A total of 290 participants were recruited in the analy- sis with a 100% response rate. According to our study the following variables were evaluated: age, BMI, marital status, sex, ethnicity, and level of education. Fifty-four percent of the participants were between the age of 18- 45. The majority of participants had a BMI of 18.5-24.9 (66.6%), while those who were married were 168 (58%). Most of the participants were female, 154 (53.1%), and participants who were Oromo were 180 (62%), while participants who were college and above were 106 (36.6%). (Table1).

| Variable | Category | Degree of POP | Total (N=290) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None-mild | Moderate-severe | Freq. % | ||

| Age | 18-45 years | 42 (59.2) | 115 (52.5) | 157 (54.1) |

| 45-59 years | 18 (25.3) | 44 (20.1) | 62 (21.4) | |

| ≥60years | 11 (15.5) | 60 (27.4) | 71 (24.5) | |

| BMI | <18.5 | 11 (15.5) | 12 (5.5) | 23 (7.9) |

| 18.5-24.9 | 45 (63.3) | 148 (67.6) | 193 (66.6) | |

| 25-30 | 10 (14.1) | 50 (22.8) | 60 (20.7) | |

| >30 | 5 (7) | 9 (4.1) | 14 (4.8) | |

| Sex | Male | 33 (46.5) | 103 (47) | 136 (46.9) |

| Female | 38 (53.5) | 116 (63) | 154 (53.1) | |

| Educational status | Illiterate | 13 (18.3) | 46 (21.1) | 59 (20.3) |

| Primary school | 8 (11.3) | 26 (11.8) | 34 (11.7) | |

| Secondary school | 29 (40.8) | 62 (28.3) | 91 (31.4) | |

| College and above | 21 (29.6) | 85 (38.8) | 106 (36.6) | |

| Marital status | Single | 17 (23.9) | 58 (26.5) | 75 (25.8) |

Table 1. The frequency, percentage of participant response and cross-tabulation of socio- demographic characteristics versus their postoperative pain after surgical procedure in Asella teaching hospital, Asella, 2023, (n=290)

Preoperative factorsBased on the report on preoperative factors, great- er numbers of respondents were kept on ASA I 172 (59.3%). Eighty-four percent of the participants did not From the intraoperative factor distribution, seven- ty-nine percent of the participants had abdominal in- cisions; on the other hand, participants who had an get preoperative analgesia, 244 (84.3%), and those who had not previous surgery were 182 (62.8%). On the other hand, eighty- one percent of the participants had preoperative anxiety. (Table2).

| Variable | Category | None-mild | Moderate-severe | Total (N=290) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA | I | 43 (60.6) | 129 (58.9) | 172 (59.3) |

| II | 28 (39.4) | 90 (41.1) | 118 (40.7) | |

| Preoperative analgesia | Yes | 9 (12.7) | 37 (16.9) | 46 (15.7) |

| No | 62 (87.3) | 182 (83.1) | 244 (84.3) | |

| Previous surgery | Yes | 27 (38) | 81 (37) | 108 (37.2) |

| No | 44 (62) | 138 (63) | 182 (62.8) |

Table 2. The frequency, percentage of participant response and cross-tabulation of Preoperative Factors versus their postoperative pain after surgical procedure in Asella teaching hospital, Asella, 2023, (n=290)

Intra operative anesthesia related factors

From the intraoperative factor distribution, seventy-nine percent of the participants had abdominal incisions; on the other hand, participants who had an incision length of ≥10cm 204 (69.3%) of patients and

patient who had not deliver nerve block 200(67%) (Table 3).

| Variable | Category | None-mild | Moderate-severe | Total (N=290) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of incision | <10cm | 28 (39.4) | 58 (26.5) | 86 (30.7) |

| ≥10 cm | 43 (60.6) | 161 (73.5) | 204 (69.3) | |

| Surgical time | <1hr | 6 (8.5) | 16 (7.3) | 22 (7.6) |

| 1-2hr | 12 (16.9) | 30 (13.7) | 42 (14.5) | |

| 2-3hr | 32 (45.1) | 100 (45.7) | 132 (45.5) | |

| >3hr | 21 (29.5) | 73 (33.3) | 94 (32.4) | |

| Type of surgery | General | 31 (43.6) | 93 (42.5) | 124 (42.7) |

| Orthopedics | 18 (25.3) | 58 (26.5) | 76 (26.2) | |

| Gynecology | 15 (21.1) | 43 (19.6) | 58 (20.1) | |

| Others | 7 (10) | 25 (11.4) | 32 (11) | |

| Duration of anesthesia | <1hr | 6 (8.5) | 16 (7.3) | 22 (7.6) |

| 1-2hrs | 12 (16.9) | 30 (13.7) | 42 (14.5) | |

| 2-3hrs | 32 (45.1) | 100 (45.7) | 132 (45.5) | |

| >3hrs | 21 (29.5) | 73 (33.3) | 94 (32.4) | |

| Type of drug for patient | Propofol | 22 (31) | 65 (29.7) | 87 (30) |

| Theopentane | 5 (7) | 15 (6.8) | 20 (6.8) | |

| Ketamine | 18 (25.3) | 56 (25.6) | 74 (25.6) | |

| Ketamine+Propofol | 26 (36.7) | 83 (37.9) | 109 (37.6) | |

| Site of incision | Abdominal | 57 (80.2) | 173 (79) | 230 (79.3) |

| Other | 14 (19.8) | 46 (21) | 60 (20.7) | |

| Intra-operative analgesia | Diclofenac | 13 (18.3) | 37 (16.9) | 50 (17.4) |

| Pethidine | 19 (26.7) | 58 (26.5) | 77 (26.5) | |

| Tramadol | 21 (29.6) | 65 (29.7) | 86 (29.6) | |

| Morphine | 10 (14.4) | 31 (14.1) | 41 (14.1) | |

| Other | 8 (11) | 28 (12.8) | 36 (12.4) | |

| Nerve Block Done | Yes | 22 (31) | 68 (31) | 90 (33) |

| No | 49 (69) | 151 (69) | 200 (67) |

Table 3. The frequency, percentage of participant response and cross-tabulation of intraoperative Factors versus their postoperative pain after surgical procedure in asella teaching hospital, Asella, 2023, (n=290)

Post-operative pain related factors

Based on the report on postoperative factors, participants who did not get postoperative analgesia were

186 (64.3), while 51 percent of the participants did not

get postoperative nerve block, and out of those who

did not get postoperative analgesia, seventy-two percent experienced moderate- severe pain. (Table 4).

| Variable | Category | None-mild | Moderate-severe | Total (N=290) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-operative Analgesics | Yes | 43 (61) | 61 (28) | 104 (36) |

| No | 28 (39) | 158 (72) | 186 (64) | |

| Type of post-op analgesics | Diclofenac | 13 (18) | 37 (17) | 50 (17) |

| Pethidine | 19 (27) | 58 (27) | 77 (27) | |

| Tramadol | 21 (30) | 65 (30) | 86 (30) | |

| Morphine | 10 (14) | 31 (14) | 41 (14) | |

| Combined | 8 (11) | 28 (13) | 36 (12) | |

| Type of nerve block | TAP | 15 (21) | 46 (21) | 61 (21) |

| Infiltration | 11 (16) | 33 (15) | 44 (15) | |

| Paravertebral | 9 (13) | 29 (13) | 38 (13) | |

| Not done | 36 (51) | 111 (51) | 147 (51) |

Table 4. The frequency, percentage of participant response and cross-tabulation of postoperative Factors versus their postoperative pain after surgical procedure in Asella teaching hospital, Asella, 2023, (n=290)

Magnitude of post-operative pain at different point in time (Statics)Study revealed that at two hours post-operative, 33% of participants responded with none to mild pain, while 67 percent responded with moderate to severe pain. At sixth hour’s post-operative 29%respond none to mild pain while 71% percent of the study participants reported experiencing moderate to severe pain and at twelve hours 25% of the study participants reported none to mild pain while 75%respond moderate to se- vere pain (Table 5).

| PAIN SCALE WITH NRS | AT 2H OF POP (%) | AT 6H OF POP (%) | AT 12H OF POP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NONE (0) | 31 (10.6) | 27 (9.3) | 18 (6.3) |

| MILD (1-3) | 64 (22.06) | 58 (20.0) | 53 (18.2) |

| MODERATE (4-7) | 186 (64.13) | 189 (65.1) | 213 (73.2) |

| SEVERE (>7) | 9 (3.1) | 16 (5.5) | 6 (2.3) |

Table 5. Pain magnitude (statics) NRS at two hours,

sixth hours and twelve hours among postoperative adult patients in Asella Teaching Hospital (n=290)

Over all moderate to severe pain magnitude

The overall magnitude of moderate to severe pain within the first 12 hours of the postoperative period between the total participants 219 (75.5%, (CI=70.2- 80.1) and no pain to mild pain were 71 (24.5%) (CI=19.8-29.8).

Factors associated with magnitude of post-operative pain within 12 hrs.

The variables in both bi-variable and multi-variable methods so as to control potential confounding factors and to determine the independent association between postoperative pain and factors of pain. On the bi-variable analysis method age, ASA status, preoperative pain, post-operative analgesia, site of incision, incision length, anesthesia type and surgery time were with (P-value 0.2) (Table 5). Finally, variables with a p-value less than 0.05 were declared as significantly associated with the outcome variable and presented with 95% CI and AOR. But only the following variables were found to have association with moderate – severe pain in the post- operative period. The present study confirmed that age ≥60 years patients POP surgery were 1.34 times more likely to have moderate to severe postoperative pain than those young adult patients who had age 45 years (AOR=1.34, 95% CI=1.15,3.94). On the other hand, participants who did not get post-operative analgesia were 5.37 times to respond moderate-severe post-operative pain than those who got the analgesia [AOR: 5.37, 95%CI: (2.77, 10.43)]. Similarly, the odds of having moderate to severe postoperative pain were 1.96 times [AOR: 1.96, 95%CI: (1.90, 4.11)] higher among participants who had incision length of > 10 cm than those with incision length of < 10 cm (Table 6)

| Variable | Category | None-mild | Moderate-severe | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <45 years | 42 (59.1) | 115 (52.6) | 1 | 1 | |

| 45-59 years | 18 (25.3) | 44 (20) | 0.89 (0.46,1.71) | 0.6 (0.26,1.33) | 0.726 | |

| ≥60 years | 11 (15.6) | 60 (27.4) | 1.99 (0.96,4.14) | 1.34 (1.15,3.94) | 0.012 | |

| Length of incision | <10cm | 28 (39.4) | 58 (26.5) | 1 | 1 | |

| ≥10cm | 43 (60.6) | 161 (73.5) | 1.8 (1.03,3.17) | 1.96 (1.90,4.11) | 0.014 | |

| Post-operative analgesics | Yes | 43 (60.6) | 61 (27.6) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 28 (39.4) | 158 (72.4) | 3.97 (2.27,6.96) | 5.37 (2.77,10.43) | 0.002 | |

| Surgical time | <60 min | 16 (22.5) | 46 (21) | 1 | 1 | |

| ≥60 min | 55 (77.5) | 173 (79) | 1.09 (0.57,2.08) | 0.17 (0.07,0.4) | ||

| Site of incision | Abdominal | 57 (80.2) | 173 (79) | 1 | 1 | |

| Other | 14 (19.8) | 46 (21) | 1.08 (0.55,2.11) | 0.44 (0.19,0.98) | 0.029 | |

| ASA | I | 43 (60.6) | 129 (58.9) | 1 | ||

| II | 28 (39.4) | 90 (41.4) | 1.07 (0.62,1.85) | 0.12 (0.015,1.04) | 0.367 |

Table 6. Bivariate and multivariate binary logistic regression: factors associated with POP in Asella teaching Hospital July–November 2023 (N =290)

Key- where AOR=adjusted odds ratio, CI=confidence interval, COR=crude odds ratio, *=Variables significant in the bi-variable logistic regression analysis (p 0.2). **=Variables significant in the multivariable logistic regression analysis (p 0.05),

This study aimed to determine the magnitude of mod- erate-to-severe pain following surgery within the first twelve hour and to verify whether or not pre-operative, intra-operative, post-operative, and demographic fac- tors are relevant explanatory factors for the magnitude of post-operative pain.

According to our study the overall magnitude of POP, 75.5% of patient report as having moderate to severe pain while the rest of the patient reports as having none to mild pain. The magnitude of the POP was 67%, 71%, and 76.0% at 2hr, 6hr, and 12 h respectively. On the bi-variable analysis method age, ASA status, pre- operative pain, post-operative analgesia, site of inci- sion, incision length, anesthesia type and surgery time were factors associated to POP. On bi-variable anal- ysis, the age ≥60 years were 1.34 times more likely to have moderate to severe postoperative pain than those young adult patients who had age between 18- 45 years (AOR=1.34, 95% CI=1.15, 3.94). Similarly, the odds of having moderate to severe postoperative pain were 1.96 times [AOR: 1.96, 95%CI: (1.90, 4.11)] higher among participants who had incision length of > 10 cm than those with incision length of < 10 cm. On the other hand, participants who did not get post-op- erative analgesia were 5.37 times to respond moder- ate-severe post-operative pain than those who got the analgesia [AOR: 5.37, 95%CI: (2.77, 10.43)].

As regard to our study the post -operative pain of patient underwent surgery at 2 hours 6 hours and 12 hours the magnitudes of levels of pain was 67% 71% and 76 % the odds of having moderate to se- vere postoperative pain were 1.96 times [AOR: 1.96, 95%CI: (1.90, 4.11)] higher among participants who had incision length of > 10 cm than those with incision length of < 10 cm in Debra tabor university Ethiopia demonstrate that the magnitude of postoperative pain was 69%, 74%, and 77.0% at 2 h, 12 h, and 24 h, re- spectively [25].

As regard to our study A Cross sectional study done in Jimma Ethiopia in 2014 by Woldehaimanot,T.et,al [20] on Postoperative Pain Management among Surgically Treated Patients revealed that the incidence of post- operative pain was reported to be 91.4% and 80.1%

of the patients were underrated indicating no progress in the area of pain treatment. The author concluded, treatment provided to patients was inadequate and not in line with international recommendations and standards.

Align with our research Incision length was also sig- nificantly associated with postoperative pain incidence during our study; participant with an incision length of > 10 cm were 2.46 times felt moderate-severe pain than those who had an incision length of < 10 cm. A cross sectional study done in Gondar, Ethiopia supported to our finding that participant with incision length > 10 cm reported that they experienced postoperative moder- ate – severe pain when compared to those with inci- sion length of <10 cm Admassu WS.et.al (2016) [7].

Study that investigated the quality of post-operative pain management in Jimma university also report- ed moderate-severe pain as 88.2% [26]. This study isagree with our study As regard with our study on “Postoperative pain is undertreated: a survey was conducted by collecting data from patient interviews and chart reviews. The study found out that 72% of the patients experience moderate to severe pain post- operatively at rest while 89.3% of patients felt pain on movement. This shows that postoperative pain is not managed adequately in the hospital [17].

In agreement with our finding, a 5-year survey on a random sample of 250 adults who had undergone sur- gical procedures in the United States showed that ap- proximately 80% of patients experienced acute pain after surgery. Of these patients, 86% had moderate, severe, or extreme pain. Experiencing postoperative pain was the most common concern in 59% of pa- tients [27].

Limitation of the studyThe main things that we suppose as limitations from our study were participant with both spinal and gener- al anesthesia were studied together and single center study were some of our study limitation.

The magnitude of moderate to severe post-operative pain was high in the first 12 hours post- operative pe- riod. History of previous surgery, post- operative an- algesia site of incision and incision length > 10 cm factors of postoperative pain after surgery. The study revealed that the overall magnitude of postoperative pain was high in the study area. This reflects attention given to postoperative pain management is low.

In accordance with our study findings, we proposed recommendations to the concerned body. All in one

health care workers, hospital management staffs and researchers are responsible for this suggestion.

For health care providers: anesthetists and other health professionals should practice Preemptive anal- gesia as it helps to reduce the severity of post-opera- tive pain. Multimodal analgesia in post- operative pain management expected to practice at recovery room and surgical ward.

For hospital management staffs: since these are the most decisive personals in the hospital, must produce a design or plan in how to treat this big problem of postoperative pain magnitude after surgery.

For researchers: we recommend researchers to carry out additional study on standard of pain management system and facility after surgery. We also suggest them to investigate magnitude of postoperative pain after surgery during general and spinal anesthesia in separate conditions.

AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologist

ASPOQ: American Society of Pain Outcome Ques- tionnaires

ATRH: Arsi teaching referral hospital

CI: Confidence Interval

GA: General Anesthesia

HCP: Health Care Professionals

MMA: Multi Modal Analgesia

OR: Odd Ratio

PACU: Post Anesthesia Care Unit

PCA: Patient-Controlled Analgesia

POD: Postoperative Days POP: postoperative pain

RA: Regional Anesthesia

SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Sciences

Rudwan Abrahim &Dawit Abdi was involved in its con- ception, design, data analysis, and interpretation, as well as the writing and editing of the paper. Barudin Fozi and Olifan

Getachew participated in the critical article draft re- view, tool evaluation, and proposal review. The final manuscript was read and approved by all authors

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of inter- est with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The study was carried out under consideration of the Helsinki Declaration of medical research ethics. Prior to the study, ethical clearance was obtained from the Departmental Research and Ethics Review Commit- tee (DRERC) of College of Health Sciences of Arsi University and the acceptance was also obtained from the study institutions (Arsi teaching hospital). More- over, full clarification about the purpose of the study was made to the Authorized person of the health facil- ity. The purpose of the study was explained to the pa- tients who were included in the study. Verbal informed consent from the patients was asked and Confiden- tiality of the information was assured by using code numbers and keeping questionnaires locked and pa- tients who were in pain during this study period were treated by their care giver, who are informed by data collector.

No specific fund was secured for this study.

Each respondent provided informed, voluntary, writ- ten, and signed consent. Participants in the study were also informed that they had the option not to an- swer any questions. Completed questionnaires were handled with care, and all access to results was re- stricted to group members only. To protect responders’ confidentially, anonymity was maintained. Prior to par- ticipating in the study, all individuals received written consent in Amharic and Afan Oromo and signed it.

Availability of Data and MaterialsThe datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request via (yasinredwan5@gmail.com)

My sincere gratitude goes out to my co-authors for their insightful criticism and ongoing assistance with this paper at every stage. Next, we would like to thank the study participants for their enthusiastic engage- ment in our research.