Strategies to Adopt in a Challenging Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Joshua Sungho Hong 1,2*,Radha Nair1

1Swan Hill District Health, Swan Hill, Victoria, Australia

2St. Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

*Corresponding Author:

Joshua Sungho Hong,

Hill District Health,

Swan Hill, Victoria,Victoria, St. Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

E-mail: joshua.hongsh@gmail.com

Received: 223 May 2025; Accepted: 16 June 2025; Published: 23 June

2025

Citation: Joshua Sungho Hong,Nair R. “Strategies to Adopt in a Challenging Laparoscopic

Cholecystectomy” J Aesthetic

Surg Med (2025): 108. DOI: 10.59462/

JASM.2.1.108

Copyright: © 2025 Joshua

Sungho Hong. This is an open-access arti cle distributed under the terms of the Creative Com mons

Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy [LC] is among the

most performed surgical procedures worldwide.

While typically straightforward, a subset of cases

presents significant technical difficulty due to

inflammation, fibrosis, or anatomical distortionfactors that dramatically increase the risk of bile

duct injury [BDI], conversion to open surgery, and

other complications. Risk factors of a challenging

cholecystectomy are male sex, older age,

obesity, acute or recurrent cholecystitis, cirrhosis,

and anatomical anomalies. A strong emphasis

is placed on hepatobiliary anatomy, including

variants of the cystic duct, cystic artery, Rouviere’s sulcus, and accessory bile

ducts, which play a critical role in surgical safety.

Mirizzi’s syndrome, though rare, represents a

particularly hazardous scenario and is discussed

in detail with respect to its classification and

operative implications. Core surgical strategies

are reviewed, highlighting the Critical View

of Safety [CVS], liberal use of intraoperative

cholangiography, and the value of intraoperative

pauses. Bailout techniques, including subtotal

cholecystectomy, fundus-first dissection, and

conversion to open surgery, are presented as

essential tools to mitigate risk when standard

dissection is unsafe or unachievable. Subtotal

cholecystectomy is recognised as a key damagecontrol option with excellent outcomes in expert

hands. Emerging adjuncts such as Indocyanine

Green [ICG] fluorescence cholangiography,

robotic surgery, and early artificial intelligence

technologies are explored for their roles in

enhancing intraoperative visualisation and

decision-making.

Ultimately, safe management of the difficult

gallbladder requires anatomical expertise, a

culture of intraoperative vigilance, and readiness

to adapt when standard approaches are

inadequate. This review aims to equip surgeons

with a structured framework to anticipate difficulty,

avoid injury, and optimise outcomes in complex

cholecystectomy scenarios.

Keywords

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy; gallbladder; Mirizzi’s syndrome; subtotal cholecystectomy; Anatomy

Introduction

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy [LC] is one of the most

common operations performed worldwide, with hundreds of thousands done annually [1]. Laparoscopic

Cholecystectomy [LC] has become the gold-standard

for treating symptomatic gallstone disease, resulting

in reduced post-operative pain, orbidity, and faster

recovery compared to open surgery [2]. Despite the

routine nature of LC, a subset of cases are deemed

“difficult” or challenging, posing significant clinical importance [3]. A difficult LC is associated with longer

operative times, higher conversion to open surgery, increased complication rates [including bile duct injury],

and extended hospital stay. Difficult LC are generally classified as the ones with severe inflammation or

scarring distorts the biliary anatomy and complicates dissection.

Situations like acute calculous cholecystitis

[especially if gangrenous or emphysematous], gallbladder perforation, Mirizzi syndrome [an impacted stone causing

biliary compression or fistula], or chronic fibrosis

can obscure Calot’s triangle and make identification

of structures challenging [4]. In one large review

[>300,000 patients], factors like acute or chronic

cholecystitis, “bad gallbladder” pathology [necrosis,

gangrene, etc.], cystic duct stones, anatomical variants, and cholecystoenteric fistulas were all linked to

difficult cholecystectomy [5]. Risk factors associated

with a difficult LC includes male sex, age, acute on

chronic cholecystitis, obesity and cirrhosis of the liver

[6-8]. LC is the leading cause of Bile Duct Injury [BDI]

in surgery, and the vast majority of major BDIs occur

in these difficult scenarios with severe inflammation or

aberrant anatomy [9]. BDIs can have significant morbidity impacts on patients. Therefore, understanding

how to predict, prepare for, and manage a challenging cholecystectomy is of a paramount clinical significance. This

paper provides a comprehensive review

of difficult cholecystectomy management-including

pertinent anatomy, evidence-based guidelines, surgical techniques, bail-out strategies, and emerging

technologies.

Hepatobiliary Anatomy and Common Variations

A thorough knowledge of the hepatobiliary anatomy

and its many variations is critical for safely navigating a difficult cholecystectomy. Key anatomic relationships in

the hepatocystic [Calot’s] triangle are paramount. The classic Calot’s triangle is bounded by the

cystic duct, common hepatic duct, and inferior surface

of the liver; it typically contains the cystic artery, lymph

node of Lund, and fatty areolar tissue [10]. In reality,

the upper boundary is the liver, and surgeons refer to

the “Calot’s” or hepatocystic triangle as the space that

must be cleared to achieve the critical view of safety

[11]. Inflammation [acute or chronic] can fill this triangle with fibrous tissue and adhesions, obscuring the

normal landmarks [12]. Scarring may adhere the gallbladder to surrounding structures, making the cystic

duct and artery difficult to identify. Important anatomical structures and variants to consider include:

Calot’s Triangle & Critical View

Proper identification of the cystic duct and cystic artery within Calot’s triangle is paramount. The “Critical

View of Safety” [CVS] technique entails clearing all fat

and fibrous tissue from Calot’s triangle, exposing the

cystic duct and artery entering the gallbladder, and

confirming the gallbladder is separated from the liver bed except at the cystic structures [13]. In difficult cases,

achieving the CVS can be challenging but remains the gold standard for avoiding misidentification

injuries. An inflamed lymph node of Lund or dense adhesions may be encountered and should be carefully

dissected to reveal the cystic artery beneath [11].

Rouviere’s Sulcus

Rouviere’s sulcus is a natural fissure on the liver’s

undersurface which is present in ~80% of individuals

that corresponds to the plane of the right porta hepatis

[14]. It runs to the right of the hepatic hilum and, when

visible, serves as a safety landmark during cholecystectomy. A general rule is to keep dissection above the

level of Rouviere’s sulcus to avoid injuring the common bile duct which lies below that plane. Drawing an

imaginary line from the sulcus to the umbilical fissure

[the R4U line] demarcates a safe zone for dissection

on the gallbladder versus the danger zone deeper toward the porta hepatis [12]. In a hostile anatomy scenario,

identifying Rouviere’s sulcus can help orient the

surgeon when usual landmarks are lost.

Cystic Artery and Variants

In about 70-80% of cases, the cystic artery arises from

the right hepatic artery and traverses within Calot’s triangle [15]. Commonly it bifurcates into superficial and

deep branches to the gallbladder. A notorious variation is a short cystic artery arising from a tortuous

right hepatic artery that loops [sometimes termed a

Moynihan’s hump or caterpillar turn]. The right hepatic

artery may be mistaken for the cystic artery because

it gives off a very short cystic branch. A catastrophic

injury could arise if one erroneously clips the right hepatic artery [16]. Therefore, caution should be taken

when the “cystic artery” seems unusually large or low

in the field, as it could potentially be an aberrant or

early-branching right hepatic artery [17].

An accessory cystic artery might arise from the gastroduodenal artery

or left hepatic artery. The cystic

artery usually passes behind the cystic duct [retroductal], but it can run anterior to the duct in around 4–5%

of cases [18].

Bile Duct Variations

There are numerous biliary tree anomalies that can

make a cholecystectomy treacherous. An aberrant

right sectoral duct [often the right posterior sectorial

duct] can sometimes empty directly into the gallbladder or cystic duct instead of the common hepatic duct.

Such a duct can be easily misidentified as the cystic

duct and mistakenly divided [19].

An

important anomaly is the presence of accessory or

aberrant bile ducts. Small subvesical bile ducts [often

called ducts of Luschka] can connect liver segments

directly to the gallbladder bed; minor ones are present

in up to 12–50% of people [20]. While they usually are tiny (<1– 2 mm) and not seen intraoperatively, if

one is relatively large and gets clipped or damaged, it

can cause a postoperative bile leak. About 0.2–2% of

cholecystectomies incur bile leaks, often from a cystic

duct stump or an unrecognised duct of Luschka [21,

22]. Indeed, the most common mechanism of major

bile duct injury is misidentification-e.g. confusing the

common bile duct or an accessory duct for the cystic

duct in an inflamed field. Low insertion of the cystic

duct or a parallel course of the cystic duct can also

cause inadvertent cut into the common duct. Routine

use of landmarks like the Rouviere’s sulcus and techniques like intraoperative cholangiography or intraoperative

usages of Indocyanine Green (ICG) can help

in better visualisation of the ductal anatomy thus allowing identification of anomalies.

Mirizzi’s Syndrome

Mirizzi’s syndrome is a rare complication of gallstone

disease where a stone becomes impacted in the cystic

duct or Hartmann’s pouch of the gallbladder and compresses the common hepatic duct. Chronic compression can lead to

erosion and formation of a cholecysto-biliary fistula between the gallbladder and common

bile duct. Mirizzi syndrome is uncommon (occurring

less than 1% in Western countries) [23]. Its presence

dramatically increases the risk of bile duct injury if unrecognised and has a reported bile duct injury rates up

to 17% when Mirizzi is undiagnosed at surgery [24].

Preoperative diagnosis can be challenging because

the presentation can mimic ordinary choledocholithiasis or cholecystitis, thus identified in only 8–62% of

cases [25]. Therefore, it is crucial to have a high index

of suspicion in patients with long-standing gallstones

who present with obstructive jaundice, cholangitis or

a shrunken gallbladder with an impacted stone in the

Hartmann’s pouch on imaging.

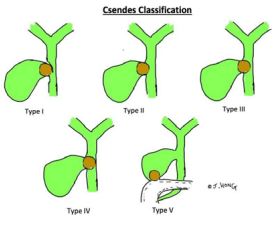

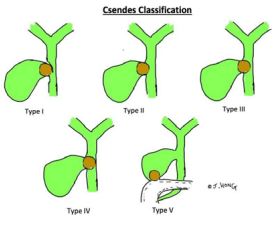

The Csendes classification is the most widely used

system to categorize Mirizzi syndrome and is based

on the presence and extent of cholecysto-biliary fistula and any cholecysto- enteric fistula [Figure 1] [26].

-

Type I: External compression of the common hepatic duct by an impacted stone in the cystic duct

or infundibulum, without any fistula. The bile duct lumen is narrowed by extrinsic pressure, but its wall is

intact.

-

Type II:A cholecysto-biliary fistula is present, with

erosion of the gallstone from the gallbladder into

the bile duct, involving less than one-third of the

bile duct circumference. There is a presence of a

small defect between the gallbladder and common

bile duct.

-

Type III:A larger cholecysto-biliary fistula involving roughly up to two-third of the bile duct

circumference. A substantial portion of the duct wall is

destroyed by the inflammatory erosion, creating a

sizable communication.

-

Type IV:A complete cholecysto-choledochal fistula replacing the common duct, involving 100% of

the bile duct circumference. The gallbladder and

bile duct form one confluent cavity due to total wall

destruction.

-

Type V:Mirizzi’s syndrome with a cholecysto-enteric fistula [a bilio-digestive fistula to

nearby viscus]. This typically results from the same inflammatory process extending to the duodenum or

colon.

Figure 1.Diagrammatic representation of Csendes Classification

Types I and II are the most common presentations,

whereas the higher types are relatively rare [23]. Mirizzi’s syndrome is usually diagnosed on imaging such

as MRCP, CT scan or ultrasound. Mirizzi’s syndrome

should be suspected if the patient has obstructive

jaundiceplus gallstones without a clear common duct

stone, or if imaging shows a stone in an infundibular

position with bile duct dilation upstream. Intraoperatively, finding a gallstone eroding into the duct or an

unusually large inflammatory mass at Calot’s triangle

signals a Mirizzi’s.

Management depends on the type: For Type I [external compression without fistula], a careful subtotal

cholecystectomy or even cholecystectomy can often

be done, removing the gallstone and gallbladder while

avoiding injury to the bile duct, sometimes combined

with a cholangiogram to confirm duct patency. For

Types II–IV [fistulas], the operation can involve a bile

duct repair. Small fistulas may be managed with choledochoplasty using a flap of cystic duct or gallbladder remnant

to close the defect. Some has proposed

a self-expanding metal stent via ERCP for small bile

duct defects [27, 28]. Larger defects might require

biliary reconstruction such as a hepaticojejunostomy.

Because the tissue is inflamed and scarred, these are

high-risk cases for bile duct injury or stricture. Some authors recommend open surgery for higher-grade

Mirizzi’s syndrome, or at least a very low threshold

to convert from laparoscopy to open, due to the advanced dissection and suturing often required. If a

cholecystoenteric fistula (Type V) is present, one must

also address the intestinal fistula and be vigilant for

gallstone ileus in the bowel.

Knowing the classifications helps in anticipating the

required surgical steps and risks. Crucially, if Mirizzi

syndrome is encountered or suspected, subtotal cholecystectomy could be performed, identification of the

bile duct and fistula extent, and often performing an

intraoperative cholangiogram or using choledochoscopy to evaluate the common duct. A difficult Mirizzi’s

case should prompt consideration of involving hepatobiliary services for ongoing management.

Strategies and Best Practices for Difficult Laparoscopic Cholecystectom

Safe technique and a systematic approach are crucial

when performing a cholecystectomy in difficult conditions. The primary goal is to avoid bile duct or vascular

injuries while successfully removing the gallbladder. A

“culture of safety” in cholecystectomy has been promoted by surgical societies [e.g. SAGES Safe Cholecystectomy

program] to systematize the practice of

safe techniques.

- Identifying and aiming to achieve the Critical View

of Safety [CVS] before dividing any duct or artery

is paramount. To attain the CVS, three criteria

must be met: [a] the hepatocystic [Calot’s] triangle

is cleared of all fat and fibrous tissue, [b] the lower third of the gallbladder is dissected off the liver

bed to expose the cystic plate, and [c] only two

structures (the cystic duct and cystic artery) are

seen entering the gallbladder, with no other connections. This creates a “funnel” or “tent” appearance

confirming the anatomy [29]. Most bile duct

injuries occur when CVS was not attained and the

wrong duct is ligated [30]. The efficacy of CVS is

well-supported: for example, one large series of

1,046 laparoscopic cholecystectomies [998 done

with CVS technique] reported zero major bile duct

injuries and only 5 minor bile leaks, with a low conversion rate of 2.7% [31].

- In any cholecystectomy, anatomical anomalies

should be considered. For example, an absent

cystic duct (cystic duct fused with the gallbladder)

or a short cystic duct can occur in chronic cholecystitis; an accessory bile duct might be draining from

the right lobe into the gallbladder; the right hepatic

artery might be anomalous. Being conscious of an

aberrant duct or vessel, it will increase vigilance to

double-check anatomy before ligation.

- A low threshold for obtaining an intraoperative

cholangiogram is advisable in difficult cases [5].

Cholangiography can opacify the biliary tree to

delineate the cystic duct/common bile duct junction and identify any stones or abnormal ducts.

Routine or selective IOC remains controversial,

but evidence suggests it can both detect common

bile duct stones and potentially alert the surgeon

to misidentification before an irreversible error is

made. Alternatives or adjuncts to IOC include laparoscopic ultrasonography or newer techniques

like near-infrared fluorescent cholangiography

with Indocyanine Green [ICG].

- An additional safety step advocated in recent

guidelines is an intraoperative pause – double

checking after dissection and identification of critical structures before ligating. This can include

having the assistant confirm the view, ensuring the

gallbladder is dissected off the liver; double confirming the CVS. Only when everyone is satisfied

should clipping and division proceed.

- Recognising the “Inflection Point” is the most important judgment in a difficult cholecystectomy.

Strasberg described an “inflection point” as the

moment where safely obtaining the critical view

is not possible, and that continuing could lead to

injury [32]. Inability to define structures after significant effort due to dense fibrosis obscuring tissue

planes [frozen Calot’s triangle], severe inflammation with purulence, or finding oneself disoriented

about the anatomy. Further dissection in Calot’s

triangle should be stopped and convert to a bailout strategy (e.g. subtotal cholecystectomy, conversion to open,

placing a cholecystostomy tube).

- Seeking help from a second experienced surgeon to assist or take over if things are extremely

challenging. A fresh perspective, or another set

of skilled hands, can sometimes navigate a tricky

dissection more easily. Referral to a hepatobiliary

service should be made early when it is beyond

the scope of one’s capabilities.

In summary, the best practices for difficult cholecystectomy center around strict adherence to safe dissection

principles, excellent visualization, liberal use

of intraoperative imaging, and the courage to halt and

choose a safer alternative when anatomy is uncertain.

Bailout Strategies for the Difficult Gallbladder

Bailout strategies are considered when conventional

dissection cannot be safely performed to avoid catastrophic injury. These techniques aim to resolve the

acute problem [remove the septic gallbladder or decompress it] while avoiding blind dissection in dangerous areas.

The main bailout options include subtotal cholecystectomy, the fundus-first [dome-down] technique, and conversion to

open surgery. In extreme

cases, aborting the cholecystectomy and performing a

cholecystostomy [drainage of the gallbladder] may be

the safest approach. Each strategy is chosen based

on intraoperative findings and the operator’s judgment.

Subtotal Cholecystectomy

Subtotal Cholecystectomy (STC) involves intentionally not removing the entire gallbladder. Indications for

STC are a hostile Calot’s triangle where the cystic duct

and artery cannot be safely isolated due to inflammation or fibrosis. The gallbladder can be truncated at

the body/fundus and leaving the portion of gallbladder

neck/cystic duct in situ which will markedly reduce the

risk of tearing the common bile duct or hepatic artery.

Two main variants are described:

- Fenestrating STC: The gallbladder is opened and

the stones and contents evacuated, and usually

the back wall of the gallbladder is left at the gallbladder fossa. The cystic duct may be left open or

suture-ligated from inside if reachable.

- Reconstituting STC: The remnant gallbladder

neck is closed by suture or stapler, reconstituting

a small “gallbladder stump” that remains. This resembles actually finishing the cholecystectomy

except that a portion of the gallbladder wall is left

attached to the cystic duct, which is closed. [33].

Both approaches avoid dissecting in the hazardous

area of the porta hepatis and a drain should be left

in-situ before bailing out.

Subtotal cholecystectomy has become one of the

most important bailouts in difficult cholecystectomy.

Evidence shows that STC dramatically lowers the risk

of bile duct injury compared to persisting with a total

cholecystectomy in severe inflammation [34]. It can

almost always be performed laparoscopically, thus

obviating the need for a large open incision in many

cases. Recent literature suggests that subtotal cholecystectomy is the single most effective bailout procedure currently

for difficult gallbladders [33]. A 2016

HPB analysis succinctly concluded that the morbidity

from bile duct injury far exceeds the morbidity from

a subtotal cholecystectomy, firmly establishing STC

as a reasonable and safe bailout strategy [35]. Bile

leakage from the stump is a known complication, especially with the fenestrating technique, so a drain is

typically left and the cystic duct may be secured with

a suture or endoloop if possible. Patients should be

informed that a remnant gallbladder remains, which in

rare cases can cause a remnant cholecystitis. However, long- term follow-up of subtotal cholecystectomy patients is

generally positive: the vast majority [over90%] have symptom resolution and avoid re-operation [36].

Fundus-First [Dome-Down] Approach

The fundus-first technique [also called dome-down

cholecystectomy] is both a strategy for difficult cases

and a potential step in a bailout. The gallbladder is dissected from the liver bed at the fundus and dissected

down towards the cystic duct. This allows early identification of the cystic duct and artery when extensive

scarring is present at Calot’s triangle. The fundus-first

dissection could allow gallbladder to be dissected except for a small stump, intentionally converting the situation

into a subtotal cholecystectomy. Key step is to

stay in the correct tissue plane during dissection – the

plane between the gallbladder serosa and the cystic

plate of the liver. Large vessels of the right portal pedicle or a hole into the common duct from the side could

be created if dissection goes into liver parenchyma or

too deep toward the hilum.

In many difficult cholecystectomies, fundus-first approach is often used in tandem

with subtotal cholecystectomy. Thus, fundus-first is an important tool in

the arsenal and can be considered a form of “bailout”

itself – an alternative dissection route that avoids

the most inflamed area initially [37]. In summary, the

dome-down technique is a valuable strategy in difficult

gallbladders, often leading to a controlled subtotal resection depending on the intra-operative assessment.

Conversion to Open Surgery

Conversion to an open cholecystectomy remains an

ever-present bailout option and is indeed the original

fail-safe plan in laparoscopic surgery. Every Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy carries a risk of conversion [a

few percent in elective cases, but significantly higher

in acute or difficult cases]. Hesitation should not be

made where laparoscopy does not allow safe progress due to severe inflammation, unclear anatomy, excessive bleeding,

or other technical impasses.

Studies have shown that conversion rates in difficult

cholecystectomy vary widely depending on the threshold of the surgeon and the patient population. Experienced

minimally invasive surgeons, using bailouts like

subtotal resection, have reported very low conversion

rates [38]. The introduction of bailout techniques like

laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy has reduced

the need for open conversion in many centers, since

the surgeon can avoid the dangerous dissection without needing to abandon laparoscopy [39]. Conversion

to open is only beneficial if the procedure can be completed safely. Therefore, it is recommended that every

surgeon should be adept at open biliary surgery or

have a colleague available who is. If a surgeon is not

comfortable with complex open biliary dissection [for

example, a laparoscopy-trained surgeon who rarely does open cases], involvement of an HPB (hepatopancreatobiliary)

specialist is wise either intraoperatively

or by early referral.

Recent Advances and Adjuncts in Difficult Cholecystectomy

Modern technology and evolving techniques are continually improving the safety of cholecystectomy, especially in

difficult scenarios. Here we discuss a few

recent advances and adjuncts that are particularly

relevant: robotic-assisted cholecystectomy, routine or

selective intraoperative cholangiography, Indocyanine

Green (ICG) fluorescence guidance and artificial intelligence.

- 1. Robotic-Assisted Cholecystectomy:

Robotic surgical systems have been increasingly applied

to cholecystectomy in the recent years. The robotic platform offers high-definition 3D visualisation

and wristed instruments that enhance dexterity compared to straight laparoscopy, which could be advantageous in

dense adhesions or awkward anatomies.

Some reports suggest that robotic cholecystectomy

can overcome difficulties related to visualisation and

instrument maneuverability in difficult gallbladders,

potentially reducing conversion rates in acute cholecystitis cases. For example, a recent study in an

emergency setting found robotic cholecystectomy had

a significantly lower risk of conversion to open surgery compared to laparoscopic in similar patients [40].

However, the data on improved outcomes with robotics are mixed. Smaller series have found the robotic approach

safe and feasible in complex cases, but

a large analysis of Medicare data reported a higher

incidence of bile duct injury with robotic cholecystectomy as compared to standard Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

[41, 42]. This might reflect the learning

curve and early adoption phase; as robotics becomes

more widespread, outcomes may improve. At present, robotic cholecystectomy is generally considered

as effective as laparoscopy for gallbladder disease,

with the potential for improved surgeon ergonomics

and precision in difficult cases. The downsides include

higher cost, longer setup time, and limited availability

in many centers. The consensus is that robotics is a

promising adjunct for difficult cholecystectomy but not

an absolute necessity.

The decision to use robotics often comes down to

surgeon preference and resource availability. robotic cholecystectomy is an emerging tool that can be

considered in difficult cases, showing some trend

toward lower conversion, but its impact on bile duct

injury rates is not clearly proven and vigilance is still

required.

- Intraoperative Cholangiography [IOC]:

Intraoperative cholangiography is a classic adjunct

rather than a new one, but it continues to be a topic of

debate and improvement in the context of difficult cholecystectomy. IOC involves cannulating the cystic duct

and injecting contrast to visualize the biliary tree under

fluoroscopy during surgery. Its utility in difficult cases

allow anatomic clarification and detection of bile duct

stones or injury-IOC can identify unsuspected common bile duct stones [in roughly 4% of cases, stones

are found on IOC in some series], allowing them to be

dealt with in the same setting (via CBD exploration or

postoperative ERCP) [43]. It can also show a leak or

extravasation if a partial injury has occurred, enabling

immediate repair.

Guidelines by organizations like SAGES and WSES

support liberal use of IOC, particularly in high-risk

cases. A large meta-analysis by Donnellan et al. of

62 studies concluded IOC is a useful tool with a high

detection rate of abnormalities and can be done selectively based on risk factors [43]. Critics of routine

IOC note it can prolong operative time and that there

is no Level-I evidence proving it reduces the incidence

of bile duct injury. However, some population studies

have observed lower BDI rates at institutions with a

policy of routine IOC, suggesting it may serve as a

safeguard. Cholangiography remains a widely used

adjunct to enhance safety, and every difficult cholecystectomy should include consideration of an IOC

at the very least. In some healthcare systems, IOC is

done routinely on all cholecystectomies as standard

practice.

- 3. ICG Fluorescence Cholangiography:

A notable recent advance in biliary surgery is the use

of indocyanine green [ICG] fluorescence imaging to

visualize bile ducts intraoperatively. ICG is a nontoxic

dye that, when injected intravenously [usually 0.25–

0.5 mg/kg a few hours or minutes before surgery], is

taken up by the liver and excreted into bile. Using a

near-infrared [NIR] camera system on laparoscopic or

robotic equipment, the biliary tree can be seen glowing [fluorescing] in real-time during the operation. Several

studies suggest that ICG enhances identification

of extrahepatic bile ducts and can help avoid misidentification injuries [44-46]. Notably, unlike an IOC which

is typically done after dissection has started, ICG can

outline ducts before any dissection – sometimes the

cystic duct is seen entering the common duct as a

fluorescent structure. A systematic review of ICG use

found that it reduced conversion rates (0.5% vs 2.5%

in non-ICG cases) and had a lower incidence of bile

duct injury (0.12% vs 1.3%) in a pooled analysis [45].

Another study in patients with acute cholecystitis after

percutaneous gallbladder drainage showed ICG fluorescence guidance significantly shortened operative

time and drastically lowered conversion to open (2.6%vs 22% without ICG) [47]. These are promising results,

indicating that fluorescence cholangiography can be

a real asset in difficult cases by making the invisible

anatomy visible. Early studies and meta- analyses

have shown reductions in operative time, conversion,

and possibly bile duct injury when ICG is used.

- Artificial Intelligence:

Although in early stages, research is underway on machine learning

tools that could, for example, highlight

biliary anatomy on the surgeon’s screen automatically

or warn when dissection is nearing a critical structure.

Some experimental systems already attempt automatic identification of the cystic duct/artery on the laparoscopic

feed [48, 49]. While not yet in clinical use

widely, these technologies represent the next frontier

in preventing errors.

Conclusion

Challenging cholecystectomy scenarios demand a

high level of surgical awareness, flexibility, and adherence to safe principles. Surgeons must know their

hepatobiliary anatomy, employ sound intraoperative

strategies, and be willing to adjust the operative plan

when managing severe cholecystitis, aberrant anatomy, or other challenging gallbladder conditions.

Key steps include obtaining the critical view of safety, utilizing cholangiography or modern fluorescence

techniques to clarify anatomy, and recognizing when

to bailout. With continued emphasis on education,

research, and adoption of best practices worldwide,

the management of challenging gallbladder cases will

continue to improve, hopefully driving complications

and conversion rates ever lower.

References

- Abdallah, Hamdy S., Mohamad H. Sedky, and Zyad H. Sedky. , “The difficult

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: a narrative review.” BMC surgery 25, no. 1 (2025): 156.

- Sugrue, Michael, Shaheel M. Sahebally, Luca Ansaloni, and Martin D. Zielinski.

“Grading operative findings at Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy-a new scoring system.”World Journal of

Emergency Surgery 10 (2015): 1-8.

- Simorov, Anton, Ajay Ranade, Jeremy Parcells, Abhijit Shaligram, Valerie Shostrom, Eugene

Boilesen, Matthew Goede, and Dmitry Oleynikov.

“Emergent cholecystostomy is superior to open cholecystectomy in extremely ill patients with acalculous

cholecystitis: a large multicenter outcome study.”

The American Journal of Surgery 206, no. 6 (2013): 935-941.

- Laws, Henry L.“The difficult cholecystectomy: problems during dissection and

extraction.”

In Seminars in Laparoscopic Surgery, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 81-91. Sage CA: Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications,

1998.

- Michael Brunt, L., Daniel J. Deziel, Dana A. Telem, Steven M. Strasberg, Rajesh Aggarwal,

Horacio Asbun, Jaap Bonjer et al.

“Safe cholecystectomy multi-society practice guideline and state-of-the-art consensus conference on

prevention of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy.”

Surgical endoscopy 34 (2020): 2827-28

- Bat, Orhan.“The analysis of 146 patients with difficult Laparoscopic

Cholecystectomy.“International journal of clinical and experimental medicine 8, no. 9 (2015): 16127.

- Kulen, Fatih, Deniz Tihan, Uğur Duman, Emrah Bayam, and Gökhan Zaim.“Laparoscopic

partial cholecystectomy: A safe and effective alternative surgical technique in “difficult

cholecystectomies“Turkish Journal of Surgery/ Ulusal Cerrahi Dergisi 32, no. 3 (2016): 185.

- Agrawal, Nikhil, Sumitoj Singh, and Sudhir Khichy.“Preoperative prediction of

difficult Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: a scoring method.”Nigerian Journal of Surgery 21, no. 2 (2015):

130-133.

- Pesce, Antonio, Teresa Rosanna Portale, Vincenzo Minutolo, Roberto Scilletta, Giovanni Li

Destri, and Stefano Puleo.“Bile duct injury during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy without intraoperative

cholangiography: a retrospective study on 1,100 selected patients.”Digestive surgery 29, no. 4 (2012): 31

- Abdalla, Sala, Sacha Pierre, and Harold Ellis.“Calot’s triangle

”Clinical anatomy 26, no. 4 (2013): 493-501.

- Andall, R. G., Petru Matusz, Maira du Plessis, Robert Ward, R. S. Tubbs, and Marios

Loukas.“The clinical anatomy of cystic artery variations: a review of over 9800 cases.

”Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 38 (2016): 529-539.

- Gupta, Vishal, and Gaurav Jain.“Safe Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Adoption of

universal culture of safety in cholecystectomy.

”World journal of gastrointestinal surgery 11, no. 2 (2019): 62.

- Strasberg, Steven M., Martin Hertl, and Nathaniel J. Soper.“An analysis of the

problem of biliary injury during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy.

”Journal of the American College of Surgeons 180, no. 1 (1995): 101-125.

- Dahmane, Raja, Abdelwaheb Morjane, and Andrej Starc.“Anatomy and surgical

relevance of Rouviere’s sulcus.”The Scientific World Journal 2013, no. 1 (2013): 254287.

- Asghar, A., A. Priya, N. Prasad, A. Patra, and D. Agrawal.“Variations in

morphology of cystic artery: systematic review and meta-analysis.

”La Clinica Terapeutica 175, no. 3 (2024).

- Kamath, B. Kavitha.“An anatomical study of Moynihan’s hump of right hepatic

artery and its surgical importance.

”Journal of the Anatomical Society of India 65 (2016): S65-S67.

- Bissinde, Evariste, Raffaele Brustia, and Eric Savier.“Early bifurcation of the

common hepatic artery: A pitfall that should be known and recognized.

”Journal of Visceral Surgery (2024).

- Fateh, Omer, Muhammad Samir Irfan Wasi, and Syed Abdullah Bukhari.“Anaotmical

variability in the position of cystic artery during laparoscopic visualization.

”BMC surgery 21 (2021): 1-5.

- Vasiliadis, Konstantinos, Elena Moschou, Sofia Papaioannou, Panagiotis Tzitzis, Albion

Totsi, Stamatia Dimou, Eleni Lazaridou, Dimitrios Kapetanos, and Christos Papavasiliou.“Isolated aberrant

right cysticohepatic duct injury during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Evaluation and treatment challenges of a

severe postoperative complication associated with an extremely rare anatomical variant.

”Annals of Hepatobiliary-pancreatic Surgery 24, no. 2 (2020): 221-227.

- Amar, Asmae Oulad, Christine Kora, Rachid Jabi, and Imane Kamaoui.“The Duct of

Luschka: an anatomical variant of the biliary tree–two case reports and a review of the literature.

”Cureus 13, no. 4 (2021).

- Spanos, Constantine P., and Theodore Syrakos.“Bile leaks from the duct of Luschka

(subvesical duct): a review.

”Langenbeck’s archives of surgery 391 (2006): 441-447.

- Tran, Thomas, and Ikram Kureshi.“Bile Leak from the Duct of Luschka: A

Multidisciplinary Approach: 561.

”Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 106 (2011): S216.

- Beltrán, Marcelo A.“Mirizzi syndrome: history, current knowledge and proposal of

a simplified classification.

”World journal of gastroenterology: WJG 18, no. 34 (2012): 4639.

- Lai, Eric CH, and Wan Yee Lau.“Mirizzi syndrome: history, present and future

development.

”ANZ journal of surgery 76, no. 4 (2006): 251-257.

- Valderrama-Treviño, Alan Isaac, Juan José GranadosRomero, Mariana Espejel-Deloiza,

Jonathan ChernitzkyCamaño, Baltazar Barrera Mera, Aranza Guadalupe Estrada-Mata, Jesús Carlos Ceballos-Villalva,

Jonathan Acuña Campos, and Rubén Argüero-Sánchez. “Updates in Mirizzi syndrome.” Hepatobiliary surgery and

nutrition 6, no. 3 (2017): 170.

- Csendes, A., J. Carlos Diaz, P. Burdiles, F. Maluenda, and O. Nava.“Mirizzi

syndrome and cholecystobiliary fistula: a unifying classification.

”British Journal of Surgery 76, no. 11 (1989): 1139-1143.

- Ayoub, R., O. Al-Shweiki, H. Bari, V. B. Giriradder, and A.

Mohamedahmed.“Management of Complex Gallstone Disease with Bouveret’s and Mirizzi Syndrome: A Case Report

with Literature Review.

”J Clin Med Surgery 5, no. 1 (2025): 1185.

- VandenDriessche, V., P. Yengue, J. Collin, and M. Lefebvre.“Combination therapy

based on SpyGlass-guided electrohydraulic lithotripsy through cholecystoduodenostomy by lumen-apposing metal

stent (SLAMS) for Mirizzi syndrome.

”Acta GastroEnterologica Belgica 87 (2024).

- Strasberg, Steven M., and Michael L. Brunt.“Rationale and use of the critical

view of safety in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy.

”Journal of the American College of Surgeons 211, no. 1 (2010): 132-138.

- Booij, Klaske AC, Philip R. de Reuver, Bram Nijsse, Olivier RC Busch, Thomas M. van

Gulik, and Dirk J. Gouma.“Insufficient safety measures reported in operation notes of complicated

laparoscopic cholecystectomies.

”Surgery 155, no. 3 (2014): 384-389.

- Avgerinos, C., D. Kelgiorgi, Z. Touloumis, L. Baltatzi, and C. Dervenis.“One

thousand laparoscopic cholecystectomies in a single surgical unit using the “critical view of safety” technique.

”Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 13 (2009): 498-503.

- Strasberg, Steven M.“A three‐step conceptual roadmap for avoiding bile duct

injury in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: an invited perspective review.

”Journal of Hepato‐Biliary‐Pancreatic Sciences 26, no. 4 (2019): 123-127.

- Elshaer, Mohamed, Gianpiero Gravante, Katie Thomas, Roberto Sorge, Salem Al-Hamali, and

Hamdi Ebdewi.“Subtotal cholecystectomy for “difficult gallbladders”: systematic review and meta-analysis.

”JAMA surgery 150, no. 2 (2015): 159-168

- Strasberg, Steven M., Michael J. Pucci, L. Michael Brunt, and Daniel J.

Deziel.“Subtotal cholecystectomy– “fenestrating” vs “reconstituting” subtypes and the prevention of bile

duct injury: definition of the optimal procedure in difficult operative conditions.

”Journal of the American College of Surgeons 222, no. 1 (2016): 89-96.

- Chavez, M., R. Figueroa, M. A. Mercado, and I. Domínguez.“Bile duct injury

associated morbidity exceeds subtotal cholecystectomy morbidity.

”HPB 21 (2019): S76-S77.

- Gross, Abby, Hanna Hong, Mir Shanaz Hossain, Jenny H. Chang, Chase J. Wehrle,

Siddhartha Sahai, Joseph Quick et al.“Clinical and patient-reported outcomes following subtotal

cholecystectomy: 10-year singleinstitution experience.

”Surgery 179 (2025): 108805.

- Garzali, Ibrahım Umar, Anas Aburumman, Yousef Alsardia, Belal Alabdallat, Saad Wraikat,

and Ali Aloun.“Is fundus first Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy a better option than conventional Laparoscopic

Cholecystectomy for difficult cholecystectomy? A systematic review and meta-analysis.

”Updates in Surgery 74, no. 6 (2022): 1797-1803.

- Le, Viet H., Dane E. Smith, and Brent L. Johnson. “Conversion of laparoscopic to

open cholecystectomy in the current era of laparoscopic surgery.

”The American Surgeon 78, no. 12 (2012): 1392-1395.

- Nassar, Ahmad HM, Hisham El Zanati, Hwei J. Ng, Khurram S. Khan, and Colin

Wood.“Open conversion in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy and bile duct exploration: subspecialisation safely

reduces the conversion rates.

”Surgical endoscopy (2022): 1-9

- Lunardi, Nicole, Aida Abou-Zamzam, Katherine L. Florecki, Swathikan Chidambaram, I-Fan

Shih, Alistair J. Kent, Bellal Joseph, James P. Byrne, and Joseph V. Sakran.“Robotic technology in

emergency general surgery cases in the era of minimally invasive surgery.

”JAMA surgery 159, no. 5 (2024):493-499.